IS GOD POSSIBLE?

Last night, at a restaurant with my wife and another couple, we ended up in conversation with a waiter named Walt. As the conversation progressed and the type of questions raised proved less familiar to the others in my party, I continued with the conversation. Truth be told, while I disagree with atheist, agnostic, and even Deist positions, I empathize with those like Walt who are genuinely searching. An intelligent young man with an English degree, he and I spent about an hour exchanging different views about God. Afterward, one of our party remarked on what she thought was my patience with Walt, though to me his congeniality never made me feel my patience was tried. “But besides,” I told her, “I’m a skeptic at heart, and so understand how difficult it is to believe.”

Although Walt and I didn’t agree about the nature of God or the Bible, our conversation reminded me of the one indispensable argument on the Christian side—that of biblical prophecy. I only wish I had brought up Daniel 9:25-26a earlier in our conversation, since this is one of the most remarkable prophecies of the Bible. When I finally did, Walt recalled his disappointment with the so-called prophecies of Edgar Cayce and Nostradamus, because of their ambiguous and general nature.

The chief reason biblical prophecy is important is because it shows the superiority of the Bible over other views. However assumptive that claim may seem to certain readers here, I urge patience while I attempt to prove this.1 These predictive prophecies show that only God knows what will happen in the future. Those who disbelieve the Bible may argue their viewpoints, and argue them well. But really they are merely showing consistency of argument, which is capable of any viewpoint. Indeed, no one can one-upmanship his opponent merely by consistent argument. For example, if someone were to say that every word symbol in speech and writing actually represents nothing, that even the whole of the universe is nothing—‘materially’ or ‘immaterially’—including his ‘readers’ and ‘listeners’ and even ‘himself,’ etc., there is hardly an argument that can be brought against him. It is not that he is right. It is that no argument can prove his consistency false to him. And so it is possible for him to verbally refute every counter-argument. And so if the Christian hopes to help him, his ‘ace-in-the-hole,’ so to speak, is an appeal to the uniqueness of biblical prophecy.

Furthermore and at the risk of sounding obvious, note that many of the prophecies of the Bible are expressed in normal language. Therefore it should be expected that it will be normal language, not mystical, which generally will also reveal details about the nature of God. For example, when in my conversation Walt claimed that Deity by definition is static perfection (the Divine Self in situ), and that therefore Deity would have no purpose to ‘move’ (i.e., change), e.g., to desire the repentance and worship of humans, I countered by pointing out that this is not a biblical view, but rather Greek. Moreover, I explained that because biblical prophecy is given in normal language and proves the superiority of Christianity, normal language, too, must be resorted to in matters of description about God. And God, or the Logos (i.e., the Rationale which preceded the world) is not as the Greeks imagined—immovable, impassive, impenetrable in transcendence and therefore essentially impersonal. Yet the Greek view is a formidable one. In short, while I could not tell Walt he was wrong because of inconsistency in his argument, I could point out that his view was inferior, because the Deity who proved himself true and superior through fulfilled prophecy declares false all other viewpoints other than those in accord with His own.

The appeal to biblical prophecy becomes even more important when one considers the limits of logic every ideology, philosophy, and theology runs up against, Christianity included. This fact was discovered by German philosopher and Einstein contemporary (and friend), Kurt Gödel. He proved that every ideology contained at some point axiomatic assumptions that were logically unprovable and thus taken on faith.2

For example, there is a famous problem in Greek philosophy which challenges Christian faith-presuppositions. It is one of Zeno’s paradoxes; here is its essence:

If between any two points of time there are infinite points of time, then change cannot happen, and therefore history is an illusion.

Christian theologians disagree with Zeno’s conclusion, though they hold to the antinomy of a God who has no beginning nor end—which implies infinity of time—yet a God who also acts in history. Consider the following illustration. If we express Time in terms of the movement of a football player running from end zone to end zone, we can say he runs the first 50 yards (half the distance) in 1/2 x, the next 25 yards (half the remaining distance) in 1/4 x, and so forth. But adding up all these fractions will never quite reach the number one. In other words, the football player will never reach the end zone if there are infinite points of time. But the problem of Time can be thought of in smaller distances as well. We can express the first step of the football player as 1/2 x + 1/4 x + 1/8 x + 1/16 x, etc., without ever reaching the number one. In other words, the football player never finishes the first step.

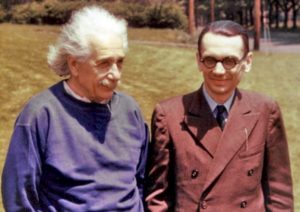

Einstein shown with Kurt Gödel on one of their regular walks

at Princeton. Both men had offices at the Institute for

Advanced Study. Einstein once told Oskar Morgenstern (a

cofounder of game theory) that he went to the Institute chiefly

to walk home with Gödel.

Even so, the first 100th part of the first step can be expressed as 1/2 x + 1/4 x + 1/8 x + 1/16 x, etc., showing the football player never even completes the hundredth part of his first step. And so forth. The result of this approach is that happening never happens. Yet in the real world we know that football players do take steps and do reach end zones. This is because of the law of multiple proportions, which rejects the idea of infinite points between any two points, and accepts that 1/2 x + 1/2 x will equal 1. So on the one hand Time seems to be infinite (because Number is assumed infinite) and therefore would deny motion to objects, yet common sense tells us there must be a fraction so small toward the end of the ‘infinite’ geometric series that it doesn’t really exist, so that the fractions can add up to the number one, enabling motion. Now, when it comes to God, the Christian believes Deity has no beginning or end. So that would seem that God’s age is infinite in number, which according to Zeno’s paradox would make motion impossible even for God. Yet fulfilled prophecy shows God does act in history. So on the one hand Time seems infinite, yet on the other hand Time seems finite, since history is accommodated.

This antinomy in Christianity of a God who existed in eternity past, yet predicates in linear time, is an inherent tension in Christianity. And no thinker has been able to explain this conundrum logically, though some have made absurd appeals to God being “outside time,” etc., which denies language (including language in the Bible) its normally understood properties, since the Bible always describes God in verbal tense. In other words, the proper Bible student appeals to normal language not just in matters of common-sense interpretation, but also, ironically, in establishing which antinomies are biblical, and which are not. In short, the few antinomies in the Bible (I count at least two, another being God’s non-determinative foreknowledge of human choice) are the exceptions that prove the (general) rule of biblical concepts accessible to human logic.

Non-Christian views, too, run into equally benumbing antinomies. The materialist (for the sake of this discussion, I include here as ‘material’ unseen things such as gravity, magnetism, air, etc.) claims there is nothing immaterial to the universe, and that even thought, emotion, and will, are somehow material in nature. Yet inevitably materialists behave discriminatory toward ‘materiality,’ proving they don’t really believe what they confess. As Hindu-trained, turned-Christian apologist, Ravi Zacharias, observes about the materialist’s hypocrisy: “Even in India we look both ways before crossing the street: For it is either the bus, or it is me; it cannot be both!” Zacharias is saying that the materialist shouldn’t care whether or not the bus hits him, since he claims materiality is all there is; therefore to assign uniqueness to some aspect of materiality on the basis of x, y, and z geophysical coordinates would be absurd. And so, no materialist has been able to solve this antinomy in his system, any more than the Christian has in his.

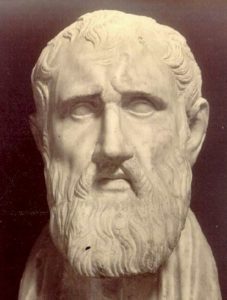

Zeno of Elea, the 5th century BC Greek

philosopher known for his paradoxes.

Aristotle called him the inventor of the

dialectic.

Now, again, the point in all this is to show that the only way out of this morass of proving which view is superior, since all views maintain consistency of verbal argument except for the few and necessary antinomies each view entails, is to concede the supernatural origin of that body of writings which contains fulfilled prophecies. For if One exists with the Power to know the future, then it seems reasonable to conclude the same One has the power to judge others according to his own standards.

Now, before we begin to look at Daniel 9:25-26a, let us admit we present a credibility problem to the one who presupposes that prophecies other than the near or self-fulfilled kind could ever be fulfilled. To such a skeptic all our reasoning will of necessity appear foolish. ‘Of necessity,’ I say, because as Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes once remarked, “when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however

improbable, must be the truth.” And so, if fulfilled prophesies are a priori dismissed as impossibilities, then whatever else remains and appeals to the skeptic will be confessed the truth, no matter how absurd it appears or how impossible it is for the skeptic to live as though it were true. I believe this is one reason why God requires belief in, not just confession of, the truth. For, again, one can verbally argue anything and remain consistent about it, while behaving in such a way that shows he really doesn’t believe what he says. As Zacharias puts it, regarding the man who would claim the world is an illusion: “Prove it to me on the 6th floor of the hotel.” But of course most skeptics are not so radical. They merely see no reason to believe in God, and so go about establishing whatever ethos they think is best for themselves and for society. Yet the danger for them is, if God has been faithful to fulfill prophecy in the past, what now of his prophecy aimed against them—that in the future he will judge men for their unbelief ?

Let us, then, examine in detail this important biblical prophecy from Daniel 9, to see if it does establish the Scripture to be uniquely superior over other writings held to be sacred or profound.

Incidentally, some of the following information gets rather technical, and so, once more, I urge patience. Finally, a word about who is my intended audience. The impetus to write about Daniel 9 came out of my conversation with Walt, in which I realized I should finally write up the results of my study (and then possibly find Walt to give him a copy of the finished work). Also, I frequently had in mind a retired Jewish dentist who, when he returned for his son’s newly-framed diploma at my picture framing shop, gave me some DVDs by the biblical critic, apostate Christian, and best-selling author, Bart Ehrman. Yet in the end, I also wrote this book as if to answer questions I think I myself would have had, were I an unbelieving skeptic.

Endnotes

1 Not a natural math/science person myself, I can empathize with those readers who might become glassy-eyed over even occasional discussions of e.g., the different reckoning systems for kingly chronologies, biblical cubits, the golden ratio, etc. But because these topics are helpful, if not also critical to proving the Daniel 9 prophecy, I hope readers will persevere.

2 Put various ways, Gödel saw that every system presupposed its own validity, was therefore tautological, and so the premise was the conclusion. Some have thought that because logical consistency eventually runs up against

propositions it cannot prove, the final answer lies in incoherence or irrationality. But even arguing this way relies at some point on an understanding of either/or (therefore, logical) definitions instead of both/and definitions,

since neither coherence nor incoherence is definably different unless at least the potential for both exists. In other words, we could not know what coherence is apart from incoherence or at least the potential for

incoherence; neither could we know incoherence apart from either coherence or the potential for coherence. Thus we understand that a proposition must be either coherent, or incoherent. Conversely, if all there were, or

could be, were incoherence, then “incoherence” would lose its meaning. That is, “coherence,” “incoherence,” “meaning,” and “meaninglessness” would all be mere sounds or scribbles and nothing more.

And so, it follows that if we are saying all systems rely at some point on incomprehensibleness, we are qualifying this to mean that the thing incomprehensive must still be comprehendible in idea. In other words, the incomprehensible thing is merely the how of the idea, not the that of the idea. For example, let us say, hypothetically, that in 1963 one person in a sci-fi book club was alone in arguing that the moon was made of cheese. Regardless that Apollo space missions would prove the person incorrect, we can say that the idea of a moon made of cheese is a comprehensible idea, however silly it is, because we grant the existence of things like moons and cheeses. But if the argument had been put forth thus: “The moon is made of cheese; yet there are no such things as moons or cheeses,” then no idea is actually being presented but merely a mouthing of word-sounds that gives us the psychological impression that a statement is being made when it is not. Such is irrationalism.

Now note that in the statement: “the moon is made of cheese; yet all moons and all cheeses are non-things,” the first ‘clause’ will sound logically comprehendible in idea until the second ‘clause’ is uttered, at which point it becomes evident that the speaker was never implying anything comprehendible in any of the words even in the first ‘clause.’ But of course most irrational ‘statements’ are more subtle than the one above, which is why they first strike the listener as plausible.

Thus, for example, when the Calvinist says that man has freedom of will yet no liberty to choose the good, he disguises the irrationality of his ‘statement’ by using synonymous phrases but treating them antonymously. Thus the phrase “freedom of will” sounds like man has a choice between good and bad, but the phrase “no liberty to choose the good” makes that impossible by implying a man’s “choice” is between one thing. And so the Calvinist leaves the impression that “freedom of will” and “liberty of choice” have transcendent meanings because of a transcendent God who, despite his transcendence, nevertheless tries to explain transcendent concepts, including, apparently, alleged meanings within irrational ‘statements.’ Readers (and hearers) hardly suspect the trick played on them. For had the Calvinist made the bald statement, “man has freedom of choice, yet man has no freedom of choice,” readers would have become immediately suspicious. And so for irrationalism to convince, it often couches itself in subtle language by using synonyms but defining them as antonyms, or by using antonyms but defining them as synonyms, such as seen in the following: “Cats are not dogs, yet all felines are canines.” If an irrationalist does opt for a bald statement, it is for shock value. Thus the title of a speech once given by deconstructionist, Jacques Derrida, at a university I attended: “My friends, there are no friends.”

Now, in true Christianity (i.e. not Calvinism) the thing incomprehensible is not so because of the principles of irrationalism, but (in part) because the idea is logically comprehensible a la “the moon is made of cheese,” while the how remains unexplained because it is incomprehensible. The biblical prophecy of Daniel 9 falls into this category of comprehendible idea yet incomprehensible execution. The idea that a Messiah is predicted to appear at the end of 483 years is comprehendible as idea, while it is incomprehensible to human logic how someone could implicitly predict, to the very day, the public presentation of a Messiah 173,880 days from a specific event (the command to rebuild the city of Jerusalem). It is not unlike Christians who understand God could change the moon into cheese if he wanted, but not know how he would do it. Which is why the Christian is called upon to believe the biblical prophet who states the idea that in the last troublous days of earth’s history God will turn the moon into blood, if that statement is not symbolic nor a metaphor. And thus logic operates in linguistic terms to support ideas, but not ideas which are no ideas because of irrationalism.

So then, if by the term “logic” we mean that which compliments “that which is real” or “that which has being,” then from the Christian standpoint we may accept by faith certain antimonies the Bible expresses, such as God’s non-determinative foreknowledge of choice, because that is what the Bible teaches. In other words, the

thing that is real for the Christian is real because God says it is real. That is not the only reason, but it is one reason. The other reasons are that God has proved his superiority through fulfilled biblical prophecy, and He demonstrates his power and goodness through creation. On these bases we therefore may accept certain other biblical doctrines beyond our comprehension, such as God’s eternality, as long as we are guided by an

interpretive method of the Bible that insists that meanings of biblical words are those meanings people granted them in the culture(s) at which point and points the Scriptures were written. There may be rare exceptions to

this, wherein God (as we shall see) uses a word as it was originally understood. An example of this is when God prophesies through Jeremiah that after 70 years of exile He will return the Jews to their land. When this

prophecy was given, a year was no longer 360 days long. Yet this was the apparent intended meaning of “year” when God spoke of it. This we know from many other factors (which this book will show), including that this

had been the meaning of the word “year” for 3,400 years until only about 1½ centuries before Jeremiah. Such an example of a meaning that is technically different than the most current vernacular is therefore not the special

pleading which seeks different meanings for words based simply on the grammatical subject. But, generally speaking, the meaning of a word is that which is commonly understood by the people. This approach is known

as the historical-grammatical method of interpretation. Such an approach will not make special pleading arguments for a word’s definition, because e.g., if words (as some would have them) can change definition when God is the subject, how can one know what any word means when God is the subject?

Note, then, that normal definitions for words define the parameters for which antinomies should be accepted, since antinomies are the exceptions which prove the general rule of language. For example, historically speaking, the word “to foreknow” in the Mediterranean Basin in the 1st century AD simply meant “to know in advance,” and never meant “to determine in advance and therefore to know in advance,” as Calvinists imply is the case when God is the grammatical subject. In biblical contexts where “human foreknowledge” and “divine foreknowledge” are described, adjectives and descriptions may modify the meaning of contexts, but the word itself will never change. For example, the word “foreknowledge” itself never changes in the phrases “human foreknowledge” and “divine foreknowledge.” In either case it simply means “to know in advance.” But differences may be revealed through descriptions surrounding the word.

I say all this to address the concern of what we should understand by the word “logic.” For if by “logic” we mean “that which makes sense,” that would be a correct definition of the word, though I hasten to add that what makes sense to God and what makes sense to us are not always the same. And so to use the phrases “human logic” and “divine logic” is correct, providing we don’t declare that what makes sense only to God is incoherent simply because humans do not understand it (in the same sense in which we would not say calculus is incoherent simply because a cat or dog does not understand it). For it is not incoherent to God. For man is not the measure of all things, but the Word is. So stated, in the Divine Mind there is no incoherence, since He understands all in all. And so it is improper to sally back and forth with atheists or agnostics about the word “logic” as though all parties agreed to the existences of both “human logic” and “divine logic.” Therefore Christians and these others cannot agree, for we Christians believe there is a God, and that the incomprehensible thing to us is sometimes the understandable and logical thing to Him.

But am I not then contradicting what I said earlier about “to foreknow”? For I said the word “to foreknow” simply meant “to know in advance,” regardless of whether the subject who was foreknowing was God or man. The answer is that the word does not change meaning, but that the Scriptures do show there is often a difference in degree between God and man. For Isaiah says, “For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways, and my thoughts than your thoughts.” (Is. 55:8) Here the words “ways” and “thoughts” mean the same thing applied to God and man, but the adjective “higher” shows a qualitative difference between God’s and man’s ways and thoughts. God’s are higher in both cases. (The same is true for logic.) But it is the surrounding description that shows us this, not anything in the actual words “ways” and “thoughts.” Even so, while God’s foreknowledge is greater in degree than man’s (as demonstrated in many passages), the word “to foreknow” is the same regardless of whether God or man is doing the foreknowing. And there is nothing in Scripture that suggests that God’s greater degree to foreknow is because He has predetermined that which he foreknows.