ENDNOTES (Ctd.)

17 The prophet Haggai shows that the Jews who returned from the exile used Nisan reckoning (see Hg. 1:1 and 2:10), and that the 6th month (Hg. 1:1) and the 9th month (Hg. 2:10) of Darius’ 2nd year were in the year beginning Nisan, 537 BC. However, as shown by the discussion in the main text, this book assumes that the author(s) of Kings and Chronicles reckoned from Tishri when in exile and/or post-exile while in a foreign land. For these writers the 2nd year of Darius (the Mede, i.e. Gobryas, the Cyrus-assigned ruler or “king” of Babylon) began Tishri, 537 BC. The latest event recorded in these books is Cyrus’ command regarding the Jewish temple in his 1st regnal year, which shortly afterward led to the end of the exile.

18 Among scholars there seems to be the general expectation that no amount of research will show that the Bible has a unified chronology. Even Christians seem to despair. For example, one fellow I found online (who was a relative expert in Hebrew) responded to my private email by saying he stays away from the “quicksand” of biblical chronology. Likewise preterists base much of their entire eschatology on the assumption that the numbers that make up a biblical chronology are to some extent metaphorical, and therefore do not prove anything against their system. I don’t even know of any dispensationalist who has thought it important enough to examine the matter in comprehensive detail, though presumably dispensationalists take the numbers literally and believe in biblical inerrancy.

19 Mention of Cyrus occurs three times in the book of Daniel (1:21; 6:26; 10:1), including mention of his 1st and 3rd years of reign. But nothing in these passages conflicts with our hypothesis that the exile lasted 2 days shy of 69 years. For in the first instance Daniel is said to have continued [even] up to the 1st year of Cyrus; in the second instance Daniel is said to have prospered in the reigns of Darius the Mede (Gobryas, a.k.a. Gubaru) and of Cyrus; and in the third instance Daniel is said to have had a vision in the first month of the 3rd year of Cyrus, by the side of the great river, Hiddekel. Daniel would have been an old man during Cyrus’ reign, and it is generally assumed he never returned to Jerusalem because of his age, though it is not known for certain.

20 Daniel records events about 46 years later than Jeremiah, whom we know used the Nisan system. But we know from Ezekiel 40:1 that the exiled Jews were using the Tishri system at least by the time Daniel was in his 50s. From Haggai we learn that the Jews who returned to their land reverted back to the Nisan system (cp. Hag. 1:1, 2:1, and 2:10), or else simply used the Nisan system that may have never been abandoned by the remnant of Jews left in the land. It is therefore important to remember when and where these two reckoning systems were in use.

Importantly, re: II Kings and its Tishri perspective: Any theologian denying that the 360-day year governs the length of the exile and the length of the year in the Daniel 9 prophecy, is under obligation to explain the ‘discrepancy’ between Jeremiah 52:28 and II Kings 24:12 (regarding which one of Nebuchadnezzar’s regnal years Jehoiachin surrendered), while also proving wrong the reasons establishing the timeline given in this book, which shows that the writer(s) of Kings and Chronicles used a consistent Tishri reckoning for both the Southern and Northern kingdoms, though those kingdoms themselves reckoned from Nisan. This alone explains the aforementioned ‘discrepancy’ according to biblical and extra-biblical records.

21 The names and order of the Jewish months (some of them Babylonian names), beginning about Mar/Apr, are: 1) Nisan (or Abib); 2) Iyar (or Ziv); 3) Sivan; 4) Tammuz; 5) Av; 6) Elul; 7) Tishri (or Tishrei); 8) Cheshvan; 9) Kislev; 10) Tevet; 11) Shevat; 12) Adar. (There was either a second Elul or second Adar when a leap month was intercalated).

22 For example, Tishri reckoning is demonstrated from statements in Nehemiah 1—2, where an event in the 9th month followed by an event in the 1st month are both said to be in Artaxerxes’ 20th year. This kind of reckoning has also been found in 5th century BC Jewish calendar records at Elephantine. The calendars show that in 14 instances the 1st of Nisan was reckoned, within a day, from (Julian) March 26 to April 24. However, the oldest of these records is from 471 BC, presumably 50+ years after Daniel would have written his book (see table of Elephantine dates at [http://www.pickle-publishing.com/papers/harold-hoehner-70-weeks.htm]). Nevertheless, statements in Ezekiel 40:1 can only be true if Tishri reckoning is invoked. And since Ezekiel 40:1 predates the Elephantine records by a full century, this means Daniel would not have been older than in his 50s when the Tishri system was in use among Jewish exiles. Therefore if we presume Daniel was in his 80s when he wrote his book, Tishri reckoning should be assumed.

23 Shea, William H. When Did the 70 Weeks of Daniel Begin? [https://adventistbiblicalresearch.org/materials/prophecy/when-did-seventy-weeks-daniel-924-begin].

24 The book of Daniel reckons years according to the 7th month, Tishri, though the Persians themselves reckoned years from spring. Both Daniel and the Persians assume ascension year reckoning. From Daniel’s exilic perspective Cyrus’ 1st year began on Tishri 1, 538 BC.

25 From all indications Cyrus, who aforetime did not know God, was by then a believer. For Ezra quotes Cyrus as knowing that the LORD God had given him all the kingdoms of the earth, and that he was instructing him [Cyrus] to build a house for him (the Lord God) in Jerusalem. (Cyrus is also a strong pre-figurement of the Messiah in Isaiah 45.) Perhaps, then, God “stirred” (see Ezra 1:1; Heb. lit. to rouse from sleep) the king’s spirit at the time of the sickness and/or death of his wife. For the Nabonidus Chronicle states that an official mourning for her took place March 20—26 (538 BC). This would have been at or near the beginning of Cyrus’ 1st year of reign (by Babylonian reckoning).

26 http:// www.livius.org/ct-cz/cyrus_I/babylon02.html+Nabonidus+chronicle+translation&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us&source=www.google.com

27 It appears God for a time may have stayed his judgment beyond when Israel deserved punishment, like when God extended to antediluvian men 120 years beyond the time when the imagination of their thoughts were already continually evil.

28 http:// www.raptureready.com/featured/ice/70-weeks-6.html+http://www.raptureread

29 There is evidence that the Jews in mid-April, 33 AD declared the 1st of Nisan based on a calculation of the astronomical new moon rather than on the visual observation of the new crescent, if the latter were their common practice. Here is the reason. If the new moon were declared only when the new crescent was seen, usually about a day later than astronomical new moon, then the 14th of Nisan in 33 AD would have fallen on a regular sabbath day instead of a Friday and thus contradicted gospel narratives. Therefore Jewish leaders would have discouraged the idea of such exertion on the sabbath, since it would have demanded that priests kill so many sacrificial lambs. This is implied in Jesus’ statement about the attitude of Jewish leaders toward the sabbath:

Or have you not read in the Law, that on the sabbath the priests in the temple break the sabbath and are innocent? (Mt. 12:5)

Obviously, the word break should be understood as placed within single quotes. That is, Jesus is not saying the priests actually broke the sabbath when they served. Rather, he is saying they are guiltless. This statement shows that Jesus accused the Jewish leaders of magnifying the sabbath out of all due proportion, to a point where they even believed priests were guilty if serving on a sabbath. (Thus Jesus elsewhere blames them for not understanding that the sabbath was made for man, and not man for the sabbath.) “Have you not read in the Law…?” says Jesus. Evidently, they had not! Jesus’ statement therefore implies the Jewish leaders would have avoided declaring Nisan’s new moon on a day they knew would lead to the exertion of priests sacrificing Passover lambs on the sabbath (seventh day). Thus the month began with astronomical new moon resulting in a Friday crucifixion of Christ on Nisan 14.

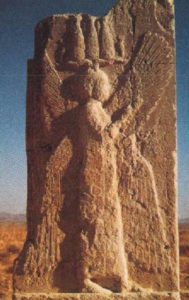

Cyrus depicted as a four-winged guardian.

30 Before proceeding to the common objections against the 445 or 444 BC view, a few introductory points should be stated. First, the edicts of the kings of the Medes and Persians were irrevocable. Therefore since Artaxerxes in his 7th year stopped the building of Jerusalem’s wall, this can only mean no decree was given prior to that which authorized its building. The beginning ‘bookend’ of 69 weeks is therefore not the building of the wall per se, but the word or decree authorizing its building. Daniel 9:25 states: “…from the going forth of the commandment…” Second, between the two sources of Josephus and the Bible, only the former makes the claim that Cyrus ordered the city to be rebuilt. But even here his testimony is at fault. For Josephus claims Cyrus authorized the rebuilding of the temple and City, yet Josephus subsequently claims Cyrus’ son and successor, Cambyses, ordered the work stopped for both temple and City (Josephus, Antiquities, XI.2:1-2), an act which would have violated the law of the Medes and Persians, which held that edicts could not be reversed.

Moving on, some claim that the Bible in Isaiah 44:28 and Isaiah 45:1ff proves Cyrus ordered Jerusalem rebuilt. But in the former instance Cyrus may be understood as merely prophesying that both temple and City would be rebuilt, only the first of which he himself would authorize. As for Isaiah 45:1ff, the chapter itself is heavily Messianic, and there is a significant pronoun change from “thee” in verse 1 to “him” in verse 13, the latter pointing, I believe, to the One who will build the City yet in the future. Again, if these passages in Isaiah proved Cyrus ordered Jerusalem rebuilt, then Artaxerxes in his 7th year could not have ordered even a temporary stop to it.

Now regarding some of the common objections against the 445 or 444 BC view (not necessarily in order of their importance):

First, it is claimed that a gap between the 69th and 70th weeks (claimed by Dispensationalists) is absurd. Various rhetorical analogies purporting to show this absurdity are not lacking, e.g., Steve Gregg of Narrow Path Ministries: “If I told my son he would get his driver’s license in three years, but then after two years told him there would be a gap of undetermined years until the third year, that would be absurd.” This approach is false,

The Arch of Titus, showing the Menorah taken during Jerusalem’s fall in 70 AD. Josephus states that when the temple was burned the gold melted downward. The soldiers dismantled the stones to retrieve the gold, and accrued so much of the precious metal that its value was halved in the economy. Of the temple buildings Jesus said, “There shall not be left here one stone upon another, that shall not be thrown down.”

however, because the analogy is not the kind which accurately represents what happened in biblical history. This can be seen from the following facts. First, it is apparent that Daniel’s 490 years is a kind of do-over for the Jews. They had failed 70 times to rest the land the 7th year of a 7-year, sabbatical cycle—and thus failed for 490 years—yet the Jews were going to be given a second chance at another 70 ‘weeks.’ But the point here is that the original 490 years pertaining to the Jews were non-contiguous. For the failure of the Jews to sabbath the land during 70 seven- year cycles did not occur in one grand lump of time. Israeli history in the Old Testament irregularly alternated between times of obedience and disobedience, as e.g. the Book of Judges shows. Therefore since the first 490-year period was interrupted, why should we suppose the do-over period could not also be interrupted?

A second objection is that Christ likened his death to 3 days and 3 nights, and that a 33 AD Friday/Sunday scenario does not accommodate a 72 hour burial. But this point is addressed in section 8 of this chapter.

A third objection is that at least some of the disobedience of the Jews likely came after the 8th century BC (i.e. in the era in which years were now composed of 365 days), since they did not enter captivity until 606 BC. But arguably the Jews were frightened into observing the sabbatical year after experiencing the earthquake/eclipse which their prophet, Amos, predicted. This ‘shock and awe’ event likely changed their attitude about keeping the sabbath year (at least in the agricultural sense), though it appears their allegiance was merely legalistic. Thus their motive was not any better than when Amos in his time observed that his countrymen kept the sabbath and new moon days while planning to commit dishonest business deals as soon as the observed days were over (Amos 8). This trend continued into the New Testament era. It is evident in the legalistic attitude Jesus encountered among the Jewish leaders regarding the weekly sabbath, who abused the true purpose of the Sabbath by sanctifying it beyond all due proportion, e.g., to a point where they believed priests were guilty if they offered sacrifice on the sabbath.

“Ecce Homo” (Behold the Man!”), by Antonio Ciseri. During the public display, Pilate learned that it was said of Jesus he was the Son of God. Alarmed, Pilate then privately questioned Jesus. Still finding no fault in him, Pilate brought him before the mob a second time, but saying, “Behold your King! ” Nevertheless, the mob cried out for Jesus’ crucifixion. This stirring painting was done by Ciseri near the end of his life, and unfortunately has an incorrect detail about the time of day Jesus was brought before the mob. Both times it was night. Nevertheless, Ciseri captures the ethos of the moment perfectly

Fourth, the claim is laid to rest that the 360-day year cannot account for why Daniel divides the weeks into 7 and 62. Here is the explanation behind the division. The seven ‘weeks’ it took to finish the building of Jerusalem would (or should) have been known to the very day by the Jews. Thus by dividing the time into 49 years, the Jews would have known what type of year God was talking about if they pondered the 70 weeks prophecy of Daniel. Or, if the Jews were already assuming they should be counting down years in 360-day increments in anticipation of the Messiah, the 49 years would have served as a ‘stop-gap’ measurement on the way to 69 weeks, assuring the Jews their assumption about counting down in 360-day increments was correct. However, it appears the Jews (generally, at least) did not avail themselves of any of these calculations. Yet as previously noted, if archaeology ever uncovers a contemporary transcription giving the completion date of the rebuilding of Jerusalem, it should be (Julian) July 23, 396 BC, which is exactly 17,640 days (7 ‘weeks’) past April 6, 444 BC (the beginning ‘bookend’ date of Daniel’s prophecy).

Fifth, the objection is often raised that a 33 AD crucifixion date does not harmonize with the commonly received 5 (or 6) BC date for the birth of Christ. This year is inferred from a statement in Josephus that (1) Herod the Great died between a lunar eclipse and the Passover, and (2) the biblical statement that all the children in Bethlehem from two years and under were killed by Herod, who sought to destroy the Christ Child. However, W.E. Filmer in his 1966 article, The Chronology of the Reign of Herod the Great (The Theological Journal, Oxford; [http://jts.oxfordjournals.org/content/XVII/2/283]) shows a number of errors that have been supposed by those advocating a 4 BC eclipse. Filmer argues for either a January 9 or December 29, 1 BC eclipse. In my opinion the former date harmonizes with Luke’s statement about Jesus being about 30 years old at the time his ministry began. It also harmonizes with Josephus’ ascension year reckoning (noted by Filmer). For presumably Luke, a senior contemporary of Josephus, would likewise have used ascension year reckoning, and thus reckoned Tiberius’ 15th year of solo reign (when John the Baptist began his ministry) to be 28/29 AD.

Sixth and very importantly, the 445 BC to 32 AD is not possible because of when the new moons in these respective years would have placed the beginning of Nisan (discussed toward the end of Chapter 2).

31 There is another type of critic whose arguments are less ridiculous but just as agenda-driven as the absurd critic.

These are they who hold some eschatological stake in Daniel’s prophecy that forces them to assume a 457 BC date instead of 444, so that the 69 weeks can end on some other date than the Day of Triumphal Entry. Their calculation involves 483 years of 365+ days each, with the crucifixion coming in 30 AD. Typically, they claim that Jesus’ baptism marks the end of the 69 weeks, with the crucifixion midway into the 70th week. Some of these believe the ‘Great Tribulation’ is metaphorically stretched to 70 AD to include the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, so that all 70 weeks of Daniel are completed history. Others believe a half week awaits fulfillment in the future. However, John in Revelation implies there are two successive 42-month or 1260-day periods, beginning with two witnesses of God who for 1260 days bring plagues upon the earth, after which they are killed by the Antichrist, who then enacts his own agenda for the same period of time (42 months). The point here is that the 360-day year is a seemingly odd perspective for a 1st century man (the apostle John) to have in a Mediterranean culture governed by the 365¼-day Julian calendar which was instituted decades before he was born. That John’s two 42-month periods of 1260 days each ought to be regarded as the final 70th week of Daniel is a fairly obvious indicator that only 69 weeks has been previously accomplished. Yet many resist this conclusion. In my opinion all these other views have one insurmountable problem. They cannot explain the eschatological implication of historical records showing the exile was barely over 69 ‘normal’ years instead of a full 70, an interval accommodating only a period of 70 years if those years are of 360 days each.

There are other problems with the 457 BC view. For example, since the decree by Cyrus in 538 BC is too early to fulfill Daniel’s prophecy, adherents of the 457 view claim that although the decree was reaffirmed twice it is really one decree, and that the start of Daniel’s prophecy should be counted from the second reaffirmation. But obviously this particular reaffirmation is chosen instead of the first reaffirmation as well as the original decree in an attempt to make the numbers work. And so it is hardly convincing. For imagine if some Islamic fellow told us Christians that a prophecy in the Koran about Muhammad was true, that it was based on a date beginning with the going forth of a command to commence the rebuilding of an Islamic city near Mecca, that the command was given and later re-ratified two times over a 90 year period, that the fulfillment required not the original command (which would obviously seem the most natural interpretation for proving the prophecy), but the re-ratification of the re-ratification. Would you believe him? Would you say, “Yes, how remarkably true”? No, of course not. You would rightly judge that he had fudged the numbers to make the ‘prophecy’ work. And yet Christians embracing the 457 BC view do this very thing.

32 On a thread I started about the superiority of 444 BC to 457 BC for the beginning bookend date for the Daniel 9 prophecy, one critic insisted Artaxerxes had reigned ca. 473 BC, years before the dates of 465 or 464 (advocated by the standard chronologies). Citing the story in Thucydides’ History of the Athenian general, Themistocles, this critic claimed an eclipse in 431 BC established an “ironclad” chronology reaching backward to 473 BC, in which the elder Themistocles sought sanctuary in Persia and so met the young King Artaxerxes. Oddly enough, this critic provided no other chronological references from Thucydides to prove his point. After asking him why he would expect readers to go through the entire History of Thucydides to calculate the alleged “ironclad” chronology themselves, and after pointing out he had not even read the NASA chart correctly for the eclipse he cited (since NASA adds a year “0” for 1 BCE, etc., ), I added the following:

As for the “ancient scholarship” you feel I’m ignoring, isn’t the shoe on the other foot? For you still haven’t attempted to refute the ancient Persian astronomical record of the positioning of two eclipses which establishes the year (465 BC) for the assassination of their King, Xerxes, after which Artaxerxes came to reign. (Telling me that I’m too influenced by Thomas Ice and Wikipedia is hardly a response.) At the risk of stating the obvious, note that astronomical records identifying specific dates in ancient history have long been the most preferred evidence among historians, much more so than the histories written by Thucydides, Josephus, etc., and for good reason.

For example, in Thucydides’ passage covering the time from the ostracizing of Themistocles’ up to his death, note that Thucydides cannot even state positively whether or not the Grecian general was successful in his bid to learn the Persian language and customs by an acceptable time, or else carry out his promise to Artaxerxes to poison himself because he could not. (This highlights the problem faced by ancient historians when they found there was insufficient written and/or oral testimony about a given event.) One gathers that Thucydides assumes the former, but because the confidence degree is not total he mentions the latter. But, then, how does that kind of “ancient scholarship” even begin to form an “ironclad” chronological framework comparable to that formed by Persian astronomical records about the positions of eclipses in the year of their king’s assassination? Again, that’s the problem with secular histories of this era; they rely on too distant sources or quasi-sources, which also means that, e.g., Thucydides’ accurate citation of an eclipse in one place in his History hardly proves that an equally accurate chronological framework attends every other statement in his work. For note that the chronology of Themistocles’ death, even to within a handful of years, is unknown to Thucydides.

Furthermore, Thucydides sometimes writes in such a way where years can pass between two events, though one might hardly suspect it unless he was aware of the general chronology. I refer to the part where Thucydides remarks on the versatile genius of Themistocles after he (allegedly, since Thucydides hedges on the matter) acquainted himself with the Persian culture and language, but then, rather abruptly, discusses his death. To hear Thucydides tell it, one might think Themistocles’ death fell on the very heels of his defection to Artaxerxes. But I gather from Wikipedia’s dates that the time from the ostracizing of Themistocles to his death were a dozen or so years apart. So, in fact, perhaps I was too hard on Thucydides to begin with. Perhaps it is not his History which is so much at fault here, but your interpretation of it….

For take particular note of statements [from Thucydides’ History] about how Themistocles was in the habit of visiting various parts on the Peloponnesian peninsula, and that in the course of all this he at some point got the scent that he was pursued. The Peloponnesian peninsula (now technically an isle, because of a canal) is over 8,300 square miles. That’s larger than a 90 mile square. So did all this take 3 months or 7 months or 19 months or 28 months or how long exactly? In short, how can one possibly judge such a matter with any certainty? And then at some subsequent point Themistocles waited for funds from friends, which implies couriers back and forth, his flight or conveyance from this point to that (“at length he arrived at Ephesus”), and so on. Of course one can suppose all this happened within months or a year at most; but is such supposition the normal approach to historical inquiry? Or is it about facts that can be proven? Facts, surely. So which are facts?—Persian astronomical records, or assumptions about how long it took to spook a guy out of an 8,000 square mile area?

Unfortunately, I often felt bound to answer such dubious critics, not because I imagined my replies would persuade them, but because I worried 3rd party readers might inexplicitly be drawn to their false reasoning. I doubt I can fully express even now the ongoing bafflement I felt when reading some of their criticisms. I have since ceased years ago to comment on public theology forums