Moreover, nothing in Josephus13 remotely suggests the courtyard had two different widths, as Kaufman assumes.

In fact, if one looks closely at Kaufman’s diagram of the temple outline, the location at which the parallel lines begin to taper behind the ‘shoulders’ of the Porch is sheer speculation. Again, there is nothing in the mishnas saying that there is any taper whatsoever, let alone a taper that begins at the east-west line of where the Holy Place meets the Holy of Holies according to Kaufman’s diagram. Furthermore, had the angles of stone remains which Kaufman found had been 7º or 11º instead of 9º, Kaufman could have simply angled the tapered lines in his diagram to ‘prove’ the evidence. In fact, most of the objects defining the 9º angled lines he shows do not even define the outline of the temple lay-out, but are outside it. Of course this criticism is somewhat incidental, since we have already shown from the Middot why a trapezoidal interpretation is not possible. But I mention it to show how a diagram can appear to support the evidence, when in reality it merely shows the plasticity of the alleged evidence.14

Moving on, note that the lion shape mentioned in Isaiah 29:1 in Middot 4:7 point 4 to which Kaufman implicitly appeals (since it is part of Middot 4:7, and so is presumably part of that which led to Maimonides’ “simple interpretation” that the temple must have been trapezoidal-shaped), refers to the city, not the temple.

Woe to Ariel, to Ariel, the city [where] David dwelt! add ye year to year; let them kill sacrifices.

The word “Ariel” means “lion of God.” But, again, there is no basis in the context of Isaiah 29 to suppose that the word “city” is acting as a metonym for the word “temple,” despite the sarcastic clause “let them kill sacrifices” (i.e., “Go ahead and sacrifice in the temple! As if that will aver judgment of the city, given the attitude of your hearts!). Nor is there any reason to suppose the Middot’s analogy of a lion is intended to imply a tapering, since elsewhere in the Middot only single width dimensions are given.

Finally, why Kaufman would think that the Jews, known for the kind of reverential or legalistic meticulousness preventing them from spelling out the name of God except as G-d, and preventing them also (in old, hand-written copies) from keeping a freshly copied manuscript of the Hebrew Scriptures if a counting of its letters in relation to the original were off by a single character, would think it acceptable

to truncate the northern end of the temple’s rectangle into a trapezoid that would have crowded around the Holy of Holies—thus forsaking the divine pattern and so resulting in a loss of the symbolic space which preserved the dignity of God (the principle in kind which King David learned at the cost of Uzzah’s life)— apparently has not crossed Kaufman’s mind. And we suspect why. Doubtless it is because he, like so many who study the logistics of a people or even his own people without a sympathetic view toward its ancient religious psyche, esteems just as little the historical statements of those ancients as he does their religious ideals. Thus more historically recent resources are generally appealed to, to advance eccentric theories. And so enter appeals to Maimonides and the Middot (though why the latter, we are at a loss to say) and, lastly here, a gold glass fragment allegedly showing the temple building in a trapezoidal area. And so the implication of the Jews’ meticulousness is cast aside, rather than to understand that the image in the gold glass fragment is simply a depiction evoking objects from the Holy Land for iconic, not mathematical purposes. Thus we have depicted in the glass fragment a temple, the trapezoidal Antonia Fortress—in which a Christian church may then have been extant if the fragment is indeed from the 4th century AD— and a menorah (depicted outside the temple!), whose iconic status so identified it with the Jews and the Holy Land that it was used to depict the capture of Jerusalem on the Arch of Titus in Rome.

ERNEST MARTIN’S VIEW OF TEMPLE LOCATION

We now leave Kaufman et al. behind to consider Ernest L. Martin’s theory of temple location outside the current walls of Jerusalem. I do not pretend that in answering Kaufman’s set of evidences I have answered all the alleged evidences of other theorists who support a temple location on the DOR platform. But I do hold that these others, like Kaufman, appeal primarily to sources other than those advanced by Ernest L. Martin, and that Martin’s sources are the historically reliable ones. And so if Martin is right, then by default these others are wrong.

Now, Martin’s evidences are available in condensed form at: [http://askelm.com/temple/t001211.htm#41]. While at times I think Martin oversells his view, I believe his general theory is correct. What follows is the gist of his argument.

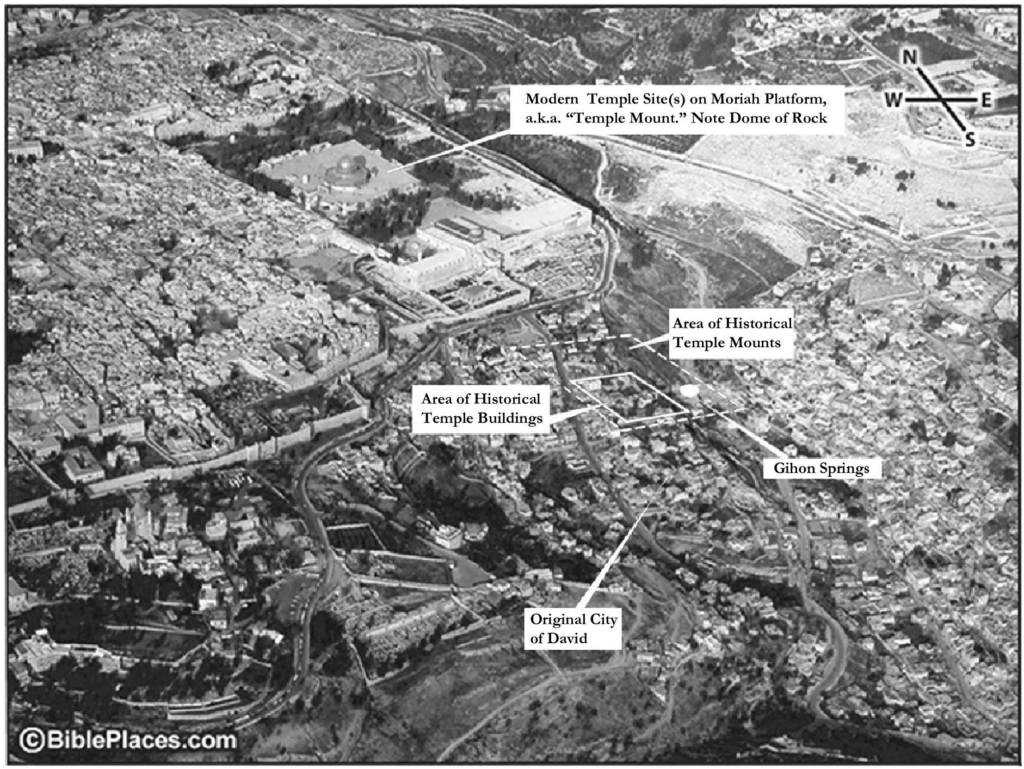

First, the temple was repeatedly described as being near the Gihon Springs (plural, Springs, but referring only to one spring which gushed intermittently, hence the name). The Gihon Springs is the only spring within a 5-mile radius of Jerusalem. Gihon lies south of the Moriah Platform on the southeast portion of the Central (Moriah) Ridge. The outer reach of this ridge’s southeastern portion was the site of the original city conquered by David, later called the City of David, or Zion. On today’s map the location of what was the City of David lies entirely outside the city walls in a suburban area. It is at this location that Jerusalem’s earliest pottery has been found.

Also, Martin points out the generally overlooked fact that David erected a tent over or near the Gihon Springs to house the Ark of the Covenant. This was where David brought the ark to rest after bringing it into Jerusalem from Kiriath-jearim. There it would remain for about 38 years until Solomon incorporated it in the new temple. The reason we know David’s tent was on or by the Gihon Springs is because Solomon was later crowned by this tent at Gihon (see I Ki. 1:33-39; I Chron. 15—16). Furthermore, there are other historical accounts showing the temple was at the Gihon Springs. One was by an Egyptian named Aristeas about 285 BC (whose writings also contain the earliest mention of the library at Alexandria). Another was by Tacitus, the Roman historian. As Martin describes these two accounts:

He [Aristeas] stated quite categorically that the Temple was located over an inexhaustible spring that welled up within the interior part of the Temple. About 400 years later the Roman historian Tacitus gave another reference that the Temple at Jerusalem had within its precincts a natural spring of water that issued from its interior. These two references are describing the Gihon Springs (the sole spring of water in Jerusalem). It was because of the strategic location of this single spring that the original Canaanite cities of “Migdol Edar” and “Jebus” were built over and around that water source before the time of King David. That sole water source was the only reason for the existence of a city being built at that spot.

Incidentally, Aristeas also stated that from the top of the wall of Jerusalem [Zion] one could look northward and easily see all of the priestly activities in the temple precincts. Thus the DOR would be disqualified as the site of the temple, because (1) a temple on the Moriah Platform would not have been by the Gihon Springs, 2) the DOR is north of the Gihon and therefore one could not look northward to where the temple was at Gihon, and 3) the DOR is 1000 feet from the Gihon, making it impossible to easily see all the priestly activities in the temple. Furthermore, though some scholars today claim Aristeas was a pseudo-writer whose aim was to glorify Judaism and that his narrative of how the Septuagint originated should be discounted, the point is irrelevant to our purposes here. For even if Aristeas were a pseudo- writer, his aim at propagandizing his compatriots would be defeated if he failed to accurately report geographical and architectural facts known by the average Jerusalemite.

Finally, Nehemiah 11:21 states: “But the Nethinims dwelt in Ophel: and Ziha and Gispa [were] over the Nethinims.” The “Nethinims” referred to were slaves or servants to the Levites and priests who served in the temple. The NASB actually translates the term into the text: “But the temple servants were living in Ophel….” Ophel was the mound area north of the original City of David and south of what is now the Moriah Platform, in the immediate vicinity of the Gihon Springs. Nehemiah 3:26 also states that these bondsmen stayed at Ophel: “Moreover the Nethinims dwelt in Ophel, unto [the place] over against the water gate toward the east, and the tower that lieth out.” Thus both verses indicate that temple servants resided south of the Moriah Platform and therefore in the immediate vicinity of the Gihon Springs, obviously because the temple was nearby where they gave service. This is yet one more indication that the temple was not located in the area of the Moriah Platform.

Second, there is the evidence that the temple was in the center of the city, whereas a location of the temple on the Moriah Platform would have meant the temple was at the city’s northern end. We know this because the 4th century BC, Greek historian Hecataeus15 of Abdera, during the time of Alexander, stated that the temple was in the center of the City, a statement supported by Psalm 116:18-19:

I will pay my vows unto the Lord now in the presence of all his people, in the courts of the Lord’s house, in the midst of thee, O Jerusalem.

And so, for this reason, too (i.e., besides the fact that the Moriah Platform is not over or near the Gihon Springs), the Moriah Platform cannot have been the site of the Temple, since it was not in the midst of the City but considerably north of it.

Third, there is the evidence of the 7th century Jewish families who were granted permission by Omar to live near the ruins of the former Jewish Temple, and who chose to live south of the Moriah Platform. This relocation of families took place after the Muslims conquered the area in 638 AD. Says Martin:

We have absolute evidence that the Jews in the seventh century knew the location of their former Temples (and their former “Western Wall” of the Holy of Holies from the Temples built in the time of Constantine and Julian). It was in the south from the Al Aksa Mosque and near the Siloam water system. The statement of fact is found in a fragment of a letter discovered in the Geniza library of Egypt now in Cambridge University in England. Notice what it states:

“Omar agreed that seventy households should come [to Jerusalem from Tiberius]. They agreed to that. After that, he asked: ‘Where do you wish to live within the city?’ They replied: ‘In the southern section of the city, which is the market of the Jews.’ Their request was to enable them to be near the site of the Temple and its gates, as well as to the waters of Shiloah, which could be used for immersion. This was granted them [the 70 Jewish families] by the Emir of the Believers. So seventy households including women and children moved from Tiberius, and established settlements in buildings whose foundations had stood for many generations” (emphasis mine [i.e., Martin’s]).

This southern area was very much south of the southern wall of the Haram (where Omar had his Al Aksa Mosque) because Professor Benjamin Mazar (when I was working with him at the archaeological excavations along the southern wall of the Haram) discovered two palatial Umayyad buildings close to the southern wall of the Haram that occupied a great deal of space south of that southern Haram wall. Those 70 families certainly had their settlement further south than the ruins of these Muslim government buildings. Also, when the Karaite Jews a century later settled in Jerusalem, they also went to this same southern area as well as adjacently across the Kidron into the Silwan area.

As Martin goes on to explain, the fact that the former Temple area was still in ruins up to the 12th century is corroborated by Maimonides (1135–1204 AD), who said that the place of the Temple was still completely in ruins, and also by Rabbi David Kimchi, shortly after Maimonides, who noted that Jerusalem was still in utter ruins, and that no Christian or Muslim had ever built over the spot where the true Temples stood.

Of course this destruction was the result of Titus’ famous victory over Jerusalem in 70 AD, at which time the entire Temple section of Jerusalem was razed to the ground. This was because the Romans, in searching for the gold that had melted down between the cracks of the stones when the Temple was set on fire, left no stone upon another. In fact, as already noted in Chapter 3, Josephus says that so much gold was taken by the soldiers that it caused the value of gold to halve in Syria. Says Martin:

This action of looking for gold by overturning the stones…left Jerusalem as a vast quarry of dislodged and uprooted stones in a state of unrecognized shambles.

There was such an abundance of various stones dislodged from their foundations that the emperor Hadrian sixty years later was able to build an entirely new city (Aelia) to the northwest of the former city by reusing many of those ruined stones. The original southeast area of Jerusalem remained an open quarry until as late as the time of Eusebius. He lamented that stones of Jerusalem and the Temple were in his day still being used for homes, temples, theatres, etc.

So why have so many scholars ended up embracing a Temple location on the Moriah Platform despite all these evidences?

It would seem one reason many scholars are misled is because they devalue Josephus because of his generally strong support of the historicity of New Testament narratives, especially in matters of archaeological detail. In fact, Josephus, if unintentionally, supports Jesus’ prediction that the Temple’s destruction would be complete, with no stone left upon another. Of course it is hard to imagine any modern scholar baldly stating that biblical prophecy is nonsense to him, since such matters are generally taken for granted within the Academy. And so, maintaining an appearance of scholarly objectivity, the oblique challenge is introduced by claiming this or that remaining fragment of wall on the Moriah Platform was part of the Herodian Temple. In other words, there are stones left upon one another. After all (we note), if this were not the case, to where would archaeology go? For there would be nothing to dig up, except perhaps, and very importantly so, the Temple’s corner foundation stones which the soldiers would not have needed to upturn, if no gold was shown to have extended all the way down the sides of those stones. But this, too—that the cornerstones might still be in situ beneath suburban Jerusalem south of the Moriah Platform—is speculation. And that is the problem for Kaufman and company. For there is no ‘smoking gun’ inscription for the Temple site as there has been for Hezekiah’s tunnel attached to the structure itself.16 And so any scholar with credentials to impress can spin his theory and find sympathetic ears among those who, like the scholar himself, find little credibility in statements by Josephus, the Bible, and historians nearer to those times.

Thus another biblical story pinpointing the location of the Temple is likewise dismissed—that the Temple was located over the threshing floor of Ornan the Jebusite (I Chron. 21—22:1, esp. 22:1). Before we look at this story in more detail, it is important to point out that a threshing floor is a flat surface of tamped, hard ground or smooth cut stone or flat timber. This is so that the parts of the grain, when separated by oxen hooves or by beating it by some other method, will not fall into cracks and crevices from which the grain would be hard to retrieve. It is also important that a threshing floor be near some wind to separate the broken grain heads as they are thrown into the air, at which point the heavier, cereal part of the grain falls down onto a blanket, while the chaff is blown away.

Now, there were unusual circumstances which led to the Temple’s location over the threshing floor of Ornan. I Chronicles 21 tells us that the Lord sent a pestilence (by way of an angel) upon Israel because of King David’s sin of numbering the people. Such numbering implied that David was placing his trust in military strength rather than in God, who had delivered him through many troubles. The pestilence kills 70,000 Israelites before the Lord changes his mind about continuing the calamity, and he does so when the angel with the sword is above the threshing floor of Ornan the Jebusite. It is then that David prays that God’s calamity only fall upon him and his father’s house, rather than upon the rest of the people of Israel. God then orders David to build an altar to the Lord on this spot. David does this and, later, relocates the Ark of the Covenant there. Significantly, when David sees that God has accepted his sacrifice, he says, “This is the house of the

Ernest L. Martin

Lord God, and this is the altar of the burnt offering of Israel” (I Chron. 22:1). And II Chronicles 3:1 affirms that this site ultimately became the location of the Temple, thus marking the space where God had demonstrated mercy: “Then Solomon began to build the house of the LORD in Jerusalem on Mount Moriah, where [the LORD] had appeared to his father David, at the place that David had prepared on the threshing floor of Ornan the Jebusite” (NIV) But a main point here is that the outcropping of the Dome of the Rock and the presumed unevenness of rock below the fill-in that levels off the surface just below the pavement of the Moriah Platform (Temple Mount, or Haram esh-Sharif) would not have easily complied with the idea of a threshing floor. (By the way, in terms of archaeology, the threshing floor of Ornan, if made of stone, may still exist, and may someday be uncovered to help establish the very spot over which the altar of the First Temple had lain.)

But, again, all such narratives seem little more than foolishness to most academicians, and so the few and low remains of walls on the Moriah Platform are pressed into service for ‘evidences’ needed to prove one theory or another about the location of the Temple. For Kaufman a particular area of worked stone just off the Platform marks a trapezoid truncation of the western end of the Hékhal, while to another academician the worked stone is a mere moat ditch running a little below and parallel to the eastern border of the trapezoidal Platform. And so forth, with one man’s treasure of evidence being another man’s trash.

But needless to say, if Martin’s position is correct, the discovery of cubit measurements by Kaufman et al based on remains on or just off the Moriah Platform have nothing at all to do with the Temple or the true measurement of the biblical cubit. In fact, it is a little amusing to find the seriousness with which Kaufman attached to the distance between ‘sockets’ related to the Temple. At one point he gives the distance to .85714 of a meter. I was impressed and not a little intimidated by Kaufman’s exactness to detail and laser- like measurements. But when I showed it to my brother he pointed out that he recognized the fraction as 6/7! And so this long fractional number Kaufman gave was merely rounded to the nearest 7th of a meter’s distance (2¾+” this way or that), as if the Hebrews were using the meter back then! But, oh, how impressive that long decimal had looked!