ENDNOTES (Ctd.)

33 see [http://www.sym454.org/mar21/].

34 The new moon determining Nisan in 4 BC was on (Julian) ca. March 27, which seasonally adjusted from the Julian Calendar to today’s calendar would make it ‘feel’ like March 24. While this makes for a relatively early Nisan, there was almost certainly no intercalated month that year, or otherwise the 1st of Nisan would have been April 26, which, even when seasonally adjusted to April 23, would have thrown forward the Passover meal to May 6, all but too late in the year. In other words, it seems very unlikely that there was an intercalated month in the year many claim was the year Herod died (4 BC). Therefore the time between the eclipse and the Passover in 4 BC would have been one, not two, months.

35 The new moon used for determining the 1st of Nisan, 1 BC fell on (Julian) March 25 or else April 23. This would equate today to about a March 22 or April 20 beginning of Nisan, though probably the former, since the latter would throw forward the Passover to (Gregorian) May 4, i.e., quite late in the year. Again, and for the same reasons, the 4 BC calendar which yields either ca. March 28 or else April 26 date for Nisan 1 all but rules out the latter date, because it places Passover on about May 6, which is even later. Jewish and Egyptian Calendars from the 5th century found at Elephantine show that in 14 instances the Jews reckoned the 1st of Nisan somewhere between (Julian) March 26 to April 24 (inclusive), or what on the Proleptic Gregorian Calendar would approximately equal March 20 to April 18. Consulting the NASA chart shows that the eclipse in 4 BC would have allowed only about one month for all the events to take place which Josephus relates, whereas the eclipse of January 9, 1 BC would allow nearly 3 months. Also, the eclipse as viewed from Jerusalem in 1 BC is total, whereas the eclipse in 4 BC is not.

36 http://www.csgnetwork.com/juliandaydate.html is one site that seems reliable. After entering a different day, you may need to move the mouse outside the calculator and left-click, rather than to press “Enter.”

37 At the risk of pressing a parable too far or drawing an analogy not originally intended, it nevertheless seems possible that the parable of the fig tree in Luke 13:6-9 may be an indicator of how long Israel remained fruitless during Jesus’ ministry. (This idea was suggested by my brother.) As far back as the Old Testament (see Is. 5) God used a simile of a husbandman—planting, tilling, and tending a fruit-bearing crop with the expectation there would be fruit—to God’s own expectation of spiritual “fruit” among the people whom he “planted” and cared for in the Promised Land. Jesus seems to have had this idea in mind when expressing the following parable:

He [Jesus] spoke also this parable; A certain man had a fig tree planted in his vineyard; and he came and sought fruit thereon, and found none. Then said he unto the dresser of his vineyard, Behold, these three years I come seeking fruit on this fig tree, and find none: cut it down; why cumber it the ground? And he answering said unto him, Lord, let it alone this year also, till I shall dig about it, and dung it: And if it bear fruit, well: and if not, then after that thou shalt cut it down.

Now, most of the early figs arrive in June/July, with the harvest in August/September. So let us say a farmer had a farmhand plant a tree in spring, and the next year the farmer looked for figs on that tree in late summer or early fall during the harvest, saw none, and came back each year for three years. That would equal three years (four times looking for fruit). But suppose he delayed cutting the tree that last fall because the farmhand wanted to aerate and fertilize the soil to see if it would help. Yet when mid- spring came the farmer still saw no visible signs of the very earliest figs known as breba, which in Israel can be seen as early as late April (especially if the tree is near a house). In such a case the duration of time the farmer waited from his first inspection of the tree would be approximately

![33 see [http://www.sym454.org/mar21/]. 34 The new moon determining Nisan in 4 BC was on (Julian) ca. March 27, which seasonally adjusted from the Julian Calendar to today’s calendar would make it ‘feel’ like March 24. While this makes for a relatively early Nisan, there was almost certainly no intercalated month that year, or otherwise the 1st of Nisan would have been April 26, which, even when seasonally adjusted to April 23, would have thrown forward the Passover meal to May 6, all but too late in the year. In other words, it seems very unlikely that there was an intercalated month in the year many claim was the year Herod died (4 BC). Therefore the time between the eclipse and the Passover in 4 BC would have been one, not two, months. 35 The new moon used for determining the 1st of Nisan, 1 BC fell on (Julian) March 25 or else April 23. This would equate today to about a March 22 or April 20 beginning of Nisan, though probably the former, since the latter would throw forward the Passover to (Gregorian) May 4, i.e., quite late in the year. Again, and for the same reasons, the 4 BC calendar which yields either ca. March 28 or else April 26 date for Nisan 1 all but rules out the latter date, because it places Passover on about May 6, which is even later. Jewish and Egyptian Calendars from the 5th century found at Elephantine show that in 14 instances the Jews reckoned the 1st of Nisan somewhere between (Julian) March 26 to April 24 (inclusive), or what on the Proleptic Gregorian Calendar would approximately equal March 20 to April 18. Consulting the NASA chart shows that the eclipse in 4 BC would have allowed only about one month for all the events to take place which Josephus relates, whereas the eclipse of January 9, 1 BC would allow nearly 3 months. Also, the eclipse as viewed from Jerusalem in 1 BC is total, whereas the eclipse in 4 BC is not. 36 http://www.csgnetwork.com/juliandaydate.html is one site that seems reliable. After entering a different day, you may need to move the mouse outside the calculator and left-click, rather than to press “Enter.” 37 At the risk of pressing a parable too far or drawing an analogy not originally intended, it nevertheless seems possible that the parable of the fig tree in Luke 13:6-9 may be an indicator of how long Israel remained fruitless during Jesus’ ministry. (This idea was suggested by my brother.) As far back as the Old Testament (see Is. 5) God used a simile of a husbandman—planting, tilling, and tending a fruit-bearing crop with the expectation there would be fruit—to God’s own expectation of spiritual “fruit” among the people whom he “planted” and cared for in the Promised Land. Jesus seems to have had this idea in mind when expressing the following parable: He [Jesus] spoke also this parable; A certain man had a fig tree planted in his vineyard; and he came and sought fruit thereon, and found none. Then said he unto the dresser of his vineyard, Behold, these three years I come seeking fruit on this fig tree, and find none: cut it down; why cumber it the ground? And he answering said unto him, Lord, let it alone this year also, till I shall dig about it, and dung it: And if it bear fruit, well: and if not, then after that thou shalt cut it down. Now, most of the early figs arrive in June/July, with the harvest in August/September. So let us say a farmer had a farmhand plant a tree in spring, and the next year the farmer looked for figs on that tree in late summer or early fall during the harvest, saw none, and came back each year for three years. That would equal three years (four times looking for fruit). But suppose he delayed cutting the tree that last fall because the farmhand wanted to aerate and fertilize the soil to see if it would help. Yet when mid- spring came the farmer still saw no visible signs of the very earliest figs known as breba, which in Israel can be seen as early as late April (especially if the tree is near a house). In such a case the duration of time the farmer waited from his first inspection of the tree would be approximately Vinedresser and the Fig Tree, by James Tissot. equivalent to the time of Christ’s ministry, about 3½ years. Thus Jesus’ parable seems to invoke an Old Testament simile that should have been familiar to his Jewish audience. Interestingly enough, the Antichrist, too, will spend 3½ years from the time of his rise as a political savior before he presents himself as the Jewish Messiah. 38 http://www.hope4israel.org/pdf/passover.pdf 39 The two lambs appear to represent the ‘bookend’ times of Christ on the cross, from the beginning of his crucifixion to his death. The date of crucifixion was May 1, 33 AD. The amount of daylight was about 13 h 22 m. Dividing 12 hours of daylight into 802 m is about 66 m 50 s. (It is assumed here that for purposes of civic time during daylight, a sundial(s) was used so the public could know what hour of the day it was. The Roman writer Censorinus says that Manius Valerius introduced sundials to Rome after his victories in Sicily. This was in the mid-3rd century BC, and so it is reasonable to suppose sundials were used throughout the Roman kingdom in Jesus’ day. Water clocks were at least one way the Romans judged time during the night. The 12 hours of darkness would have been of less duration than the hours of daylight during the Passover in 33 AD. According to Redshift 6 software Sunrise at Jerusalem came 03:09:25 UT and sunset at 04:30:53 UT. Adding 2 h 20 m 55 s for local time and allowing for refraction of about 4 m 43 s before sunrise and also after sunset gives us daylight from 5:25:03 AM to 6:56:31 PM, for a total daylight of 13h 33 m 28 s. We divide this by 12 h with the result that each hour lasted 1 h 7 m 47 s. The gospels give four hours related to the resurrection. John says that after Pilate had questioned Jesus he brought him out the second time to the crowd at about the 6th hour, i.e., one ‘hour’ before sunrise, or 4:17 AM. John reckons from midnight according to Roman reckoning. The synoptic gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke all reckon from Jewish time (the 12 hours beginning with either sunset or sunrise, in this case sunrise). Mark states that the crucifixion began at the 3rd hour and Matthew, Mark, and Luke state that there was darkness at or about the 6th hour until the 9th hour. At the end of the 9th hour Christ died. The word for “unto” or “until” the 9th hour is the Greek word heos which we will study in Chapter 7, and which always, or virtually always, means through the time of, hence, through the entirety of the 9th hour. Although we are not insisting here that the specific hours given by the gospels are generally intended to mean to-the-second or to-the- minute, we give the times for the 6th hour of John and the 3rd hour of Mark and the 6th and 9th hours of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Rounding to approximately the nearest minute or so, the sixth hour of John, when Pilate brought Jesus out to the crowd after speaking to him, was an hour before daybreak, i.e., 4:17 AM. The 3rd hour spoken of by Mark, in which Jesus’ crucifixion began, ran from about 7:41 AM to 8:49 AM. The darkness which Matthew, Mark, and Luke said covered the land from the 6th hour through all of the 9th hour, began somewhere between 11:02 AM and 12:09 PM, and ran through 3:35 PM. At this point the darkness lifted and the daylight returned until the sun set at 6:57 PM, which marked the beginning of the 15th of Nisan. I have given these times mostly for curiosity’s sake, but also to show there was time to bury Jesus and for the women to prepare spices by sundown, to be used after the 15th of Nisan was over. 40 As Norman B. Harrison states in His Book: or Scripture in Scripture (p. 51), though mistaking wheat for what in fact was barley: This [First-Fruits] feast foreshadowed the resurrection of Christ from the dead, signifying also His acceptance for us and our acceptance in Him. For this purpose a sheaf of wheat was taken from the field, typifying the new life from the “grain of wheat” under necessity of falling into the ground and dying. It was the early grain, in the process of maturing—a promise of the harvest to be. So “now hath Christ been raised from the dead, the first-fruits of them that are asleep” (1 Cor. 15:20, R.V.). 41 Josephus. The Complete Works. Chapter 10. [http://www.ccel.org/ccel/josephus/complete.ii.iv.x.html]. Josephus says: But on the second day of unleavened bread, which is the sixteenth day of the month, they first partake of the fruits of the earth, for before that day they do not touch them. And while they suppose it proper to honor God, from whom they obtain this plentiful provision, in the first place, they offer the first-fruits of their barley…. 42 The origin of the first day of unleavened bread dates back to the Exodus. The Israelites were told by God not to bake bread with leaven so that it would cook more quickly and could be eaten with haste. This was done so they could leave hurriedly. 43 http://www.hope4israel.org/pdf/passover.pdf 44 Translators tend to also translate the Greek “de” as “now,” “and,” etc., under the assumption that any change in the narrative, even of a temporal nature, such as “now,” is an adversative (or “weak adversative”). To date, although I have certainly not checked all the contexts surrounding all the occurrences of “de” in the New Testament (there are some 1,870 of them), I disagree with the lexicons on this issue. For example, despite the frequent appearance of “de” throughout much of Matthew 1’s genealogy, which at first glance would seem most strongly to support the idea that “de” is acting merely as a weak adversative of temporal change (e.g., “now,” “then”), arguably a greater adversative is Matthew’s intention, since before this long list he begins his gospel by saying that Jesus Christ—lit. Yahweh Anointed—is the son of David, the son of Abraham. Such a statement would shock the average Jewish reader wise enough to understand the usual difference between Yahweh’s Anointed and Yahweh himself, i.e., persons like Saul or David who, though just men, were the Anointed of Yahweh, in contrast to Jesus who, though he too was the Anointed of Yahweh, was Yahweh himself. And so, arguably, Matthew’s genealogy from Abraham onward, in which “de” so frequently appears, may simply be Matthew’s repeated way of stating the nevertheless aspect of Jesus also being human despite his having preceded all humanity, being Yahweh. (Christ himself rhetorically asked his detractors why the Scripture spoke of the Lord as both David’s Lord yet also his Son.) In other words, Matthew 1:1ff may be understood thus: “The genealogy of Jesus Christ [lit. Yahweh Anointed]—son of David, son of Abraham. Yet Abraham begat Isaac, yet Isaac begat Jacob…” etc., thus pointing to the process of human progeny which one would not naturally think would be the lineage of the Lord himself, who preceded man. It seems Matthew is underscoring the surprise that God would be willing to take on flesh, an idea reprehensible both to the many Jews who believed the substance of God was too unique for that possibility, and to the Greeks and Hellenized Jews who believed the Perfect Forms (e.g., as Plato defined them) were not present on this earth. Hence the Jews’ statement to Jesus that they should stone him because, though a man, he made himself out to be God (Jn. 10:33). But even if the scholars are correct that “de” may at times be understood as defining only a temporal change in the narrative, there is no reason not to translate Greek “de” as “yet,” or “despite,” etc., if the context can be shown to support a more intense adversity, since that is how the word most frequently functions. The problem, then, is that translators have routinely not examined biblical passages in which “de” appears, to see if in each case a greater adversity is present in the writer’s mind than a simple temporal change. Though to date I have only examined a fraction of the “de” occurrences, I have still not found a single instance that in my opinion translators had to render as merely a temporal change in the narrative. At any rate, where a greater adversity is present, the rendering should be “yet,” “despite,” etc., instead of “and” or “now.” With this one change to our translations these verses would lose that concrete tone of understatement so characteristic of the Englished gospels. The result would be something closer to the original Greek text—a point/counter-point, interactive style, forming a lively and intense narrative. 45 By “eat” I do not mean anything of the Catholic idea of taking the Eucharist, but that Christ spoke only symbolically of his body given in sacrifice for our sins. The book of Hebrews tells us Christ suffered once for sins (Heb. 10:10). Yet the Mass implies that the suffering of Christ is repeated. Also, if Christ were truly present in the bread and wine, why did Christ instruct his disciples to “do this in remembrance of Me”? For one only remembers a person when he is not present. Yet the Catholic idea would have Jesus to be bodily present in the bread and the wine. But if there still be doubt about the matter, we must recall that the writer of Hebrews contrasts the Old Covenant system and its continual sacrifices by priests, to Christ who suffered once for all sins. “Every priest stands daily ministering and offering time after time the same sacrifices, which can never take away sins; but He, having offered one sacrifice for sins for all time, sat down at the right hand of God” (see Heb. 10:11-12). The Temple Precinct as drawn by Newton in Babson MS 0434 (courtesy of Huntingdon Library)](https://danielgracely.com/rockpapershivers/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/fig-tree-300x221.jpg)

Vinedresser and the Fig Tree, by James Tissot.

equivalent to the time of Christ’s ministry, about 3½ years. Thus Jesus’ parable seems to invoke an Old Testament simile that should have been familiar to his Jewish audience. Interestingly enough, the Antichrist, too, will spend 3½ years from the time of his rise as a political savior before he presents himself as the Jewish Messiah.

38 http://www.hope4israel.org/pdf/passover.pdf

39 The two lambs appear to represent the ‘bookend’ times of Christ on the cross, from the beginning of his crucifixion to his death. The date of crucifixion was May 1, 33 AD. The amount of daylight was about 13 h 22 m. Dividing 12 hours of daylight into 802 m is about 66 m 50 s. (It is assumed here that for purposes of civic time during daylight, a sundial(s) was used so the public could know what hour of the day it was. The Roman writer Censorinus says that Manius Valerius introduced sundials to Rome after his victories in Sicily. This was in the mid-3rd century BC, and so it is reasonable to suppose sundials were used throughout the Roman kingdom in Jesus’ day. Water clocks were at least one way the Romans judged time during the night. The 12 hours of darkness would have been of less duration than the hours of daylight during the Passover in 33 AD. According to Redshift 6 software Sunrise at Jerusalem came 03:09:25 UT and sunset at 04:30:53 UT. Adding 2 h 20 m 55 s for local time and allowing for refraction of about 4 m 43 s before sunrise and also after sunset gives us daylight from 5:25:03 AM to 6:56:31 PM, for a total daylight of 13h 33 m 28 s. We divide this by 12 h with the result that each hour lasted 1 h 7 m 47 s. The gospels give four hours related to the resurrection. John says that after Pilate had questioned Jesus he brought him out the second time to the crowd at about the 6th hour, i.e., one ‘hour’ before sunrise, or 4:17 AM. John reckons from midnight according to Roman reckoning. The synoptic gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke all reckon from Jewish time (the 12 hours beginning with either sunset or sunrise, in this case sunrise). Mark states that the crucifixion began at the 3rd hour and Matthew, Mark, and Luke state that there was darkness at or about the 6th hour until the 9th hour. At the end of the 9th hour Christ died. The word for “unto” or “until” the 9th hour is the Greek word heos which we will study in Chapter 7, and which always, or virtually always, means through the time of, hence, through the entirety of the 9th hour. Although we are not insisting here that the specific hours given by the gospels are generally intended to mean to-the-second or to-the- minute, we give the times for the 6th hour of John and the 3rd hour of Mark and the 6th and 9th hours of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Rounding to approximately the nearest minute or so, the sixth hour of John, when Pilate brought Jesus out to the crowd after speaking to him, was an hour before daybreak, i.e., 4:17 AM. The 3rd hour spoken of by Mark, in which Jesus’ crucifixion began, ran from about 7:41 AM to 8:49 AM. The darkness which Matthew, Mark, and Luke said covered the land from the 6th hour through all of the 9th hour, began somewhere between 11:02 AM and 12:09 PM, and ran through 3:35 PM. At this point the darkness lifted and the daylight returned until the sun set at 6:57 PM, which marked the beginning of the 15th of Nisan. I have given these times mostly for curiosity’s sake, but also to show there was time to bury Jesus and for the women to prepare spices by sundown, to be used after the 15th of Nisan was over.

40 As Norman B. Harrison states in His Book: or Scripture in Scripture (p. 51), though mistaking wheat for what in fact was barley:

This [First-Fruits] feast foreshadowed the resurrection of Christ from the dead, signifying also His acceptance for us and our acceptance in Him. For this purpose a sheaf of wheat was taken from the field, typifying the new life from the “grain of wheat” under necessity of falling into the ground and dying. It was the early grain, in the process of maturing—a promise of the harvest to be. So “now hath Christ been raised from the dead, the first-fruits of them that are asleep” (1 Cor. 15:20, R.V.).

41 Josephus. The Complete Works. Chapter 10. [http://www.ccel.org/ccel/josephus/complete.ii.iv.x.html]. Josephus says:

But on the second day of unleavened bread, which is the sixteenth day of the month, they first partake of the fruits of the earth, for before that day they do not touch them. And while they suppose it proper to honor God, from whom they obtain this plentiful provision, in the first place, they offer the first-fruits of their barley….

42 The origin of the first day of unleavened bread dates back to the Exodus. The Israelites were told by God not to bake bread with leaven so that it would cook more quickly and could be eaten with haste. This was done so they could leave hurriedly.

43 http://www.hope4israel.org/pdf/passover.pdf

44 Translators tend to also translate the Greek “de” as “now,” “and,” etc., under the assumption that any change in the narrative, even of a temporal nature, such as “now,” is an adversative (or “weak adversative”). To date, although I have certainly not checked all the contexts surrounding all the occurrences of “de” in the New Testament (there are some 1,870 of them), I disagree with the lexicons on this issue. For example, despite the frequent appearance of “de” throughout much of Matthew 1’s genealogy, which at first glance would seem most strongly to support the idea that “de” is acting merely as a weak adversative of temporal change (e.g., “now,” “then”), arguably a greater adversative is Matthew’s intention, since before this long list he begins his gospel by saying that Jesus Christ—lit. Yahweh Anointed—is the son of David, the son of Abraham. Such a statement would shock the average Jewish reader wise enough to understand the usual difference between Yahweh’s Anointed and Yahweh himself, i.e., persons like Saul or David who, though just men, were the Anointed of Yahweh, in contrast to Jesus who, though he too was the Anointed of Yahweh, was Yahweh himself. And so, arguably, Matthew’s genealogy from Abraham onward, in which “de” so frequently appears, may simply be Matthew’s repeated way of stating the nevertheless aspect of Jesus also being human despite his having preceded all humanity, being Yahweh. (Christ himself rhetorically asked his detractors why the Scripture spoke of the Lord as both David’s Lord yet also his Son.) In other words, Matthew 1:1ff may be understood thus: “The genealogy of Jesus Christ [lit. Yahweh Anointed]—son of David, son of Abraham. Yet Abraham begat Isaac, yet Isaac begat Jacob…” etc., thus pointing to the process of human progeny which one would not naturally think would be the lineage of the Lord himself, who preceded man. It seems Matthew is underscoring the surprise that God would be willing to take on flesh, an idea reprehensible both to the many Jews who believed the substance of God was too unique for that possibility, and to the Greeks and Hellenized Jews who believed the Perfect Forms (e.g., as Plato defined them) were not present on this earth. Hence the Jews’ statement to Jesus that they should stone him because, though a man, he made himself out to be God (Jn. 10:33).

But even if the scholars are correct that “de” may at times be understood as defining only a temporal change in the narrative, there is no reason not to translate Greek “de” as “yet,” or “despite,” etc., if the context can be shown to support a more intense adversity, since that is how the word most frequently functions. The problem, then, is that translators have routinely not examined biblical passages in which “de” appears, to see if in each case a greater adversity is present in the writer’s mind than a simple temporal change. Though to date I have only examined a fraction of the “de” occurrences, I have still not found a single instance that in my opinion translators had to render as merely a temporal change in the narrative. At any rate, where a greater adversity is present, the rendering should be “yet,” “despite,” etc., instead of “and” or “now.” With this one change to our translations these verses would lose that concrete tone of understatement so characteristic of the Englished gospels. The result would be something closer to the original Greek text—a point/counter-point, interactive style, forming a lively and intense narrative.

45 By “eat” I do not mean anything of the Catholic idea of taking the Eucharist, but that Christ spoke only symbolically of his body given in sacrifice for our sins. The book of Hebrews tells us Christ suffered once for sins (Heb. 10:10). Yet the Mass implies that the suffering of Christ is repeated. Also, if Christ were truly present in the bread and wine, why did Christ instruct his disciples to “do this in remembrance of Me”? For one only remembers a person when he is not present. Yet the Catholic idea would have Jesus to be bodily present in the bread and the wine. But if there still be doubt about the matter, we must recall that the writer of Hebrews contrasts the Old Covenant system and its continual sacrifices by priests, to Christ who suffered once for all sins. “Every priest stands daily ministering and offering time after time the same sacrifices, which can never take away sins; but He, having offered one sacrifice for sins for all time, sat down at the right hand of God” (see Heb. 10:11-12).

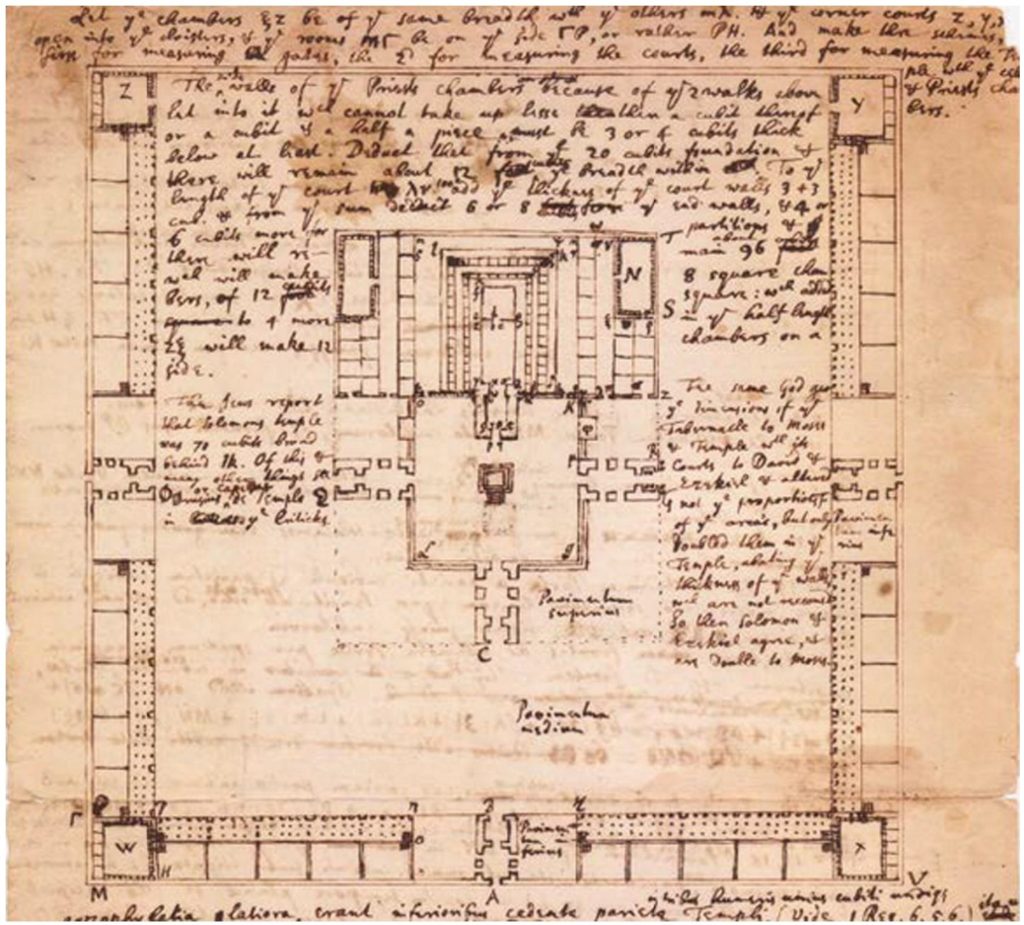

The Temple Precinct as drawn by Newton in Babson MS 0434 (courtesy of Huntingdon Library)

The Temple Precinct as drawn by Newton in Babson MS 0434 (courtesy of Huntingdon Library)