(d) THE 10TH OF NISAN IN RELATION TO THE PREPARATION OF THE LAST SUPPER AND PASSOVER

I quote Gregg and mention the other points above to show why we can now work backwards from Mark’s chronology from the crucifixion to see the Passover and preparation in relation to the 10th of Nisan—that is, exactly when the lamb was set apart for sacrifice. And we will see from Mark’s chronology that the 10th of Nisan, 33 AD coincides with the day of the Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem. This was when Jesus was presented as the Lamb of God set apart for sacrifice, to take away the sins of the world.

Working backwards, then, Mark 14:1 taken together with Matthew 26:2 yield the statement that after two days would be the Passover. Let us look first at Mark 14:1:

After two days was [the feast of] the passover, and of unleavened bread: and the chief priests and the scribes sought how they might take him by craft, and put [him] to death.

Again, the Passover and the 1st day of unleavened bread fell on the 15th of Nisan (see Lev. 23:5). Mark introduces his verse with the Greek word “de,” an adversative which (again) in my opinion was wrongly translated by the KJV to mean “after.” Rather, the word “de” means yet, but, despite, nevertheless, etc., and serves as a connecting bridge contrasting something previously mentioned to what is about to be stated. In fact, at the end of the previous chapter Mark has just recorded Jesus’ command that his followers watch. And so what Mark is contrasting is the disciples of Jesus who watch for signs of his return with glad anticipation of their reunion with him, versus the chief priests and scribes who were watching for Jesus so that they might kill him!

Now, compared to Mark 14:1, Matthew 26:2 is the one which is more clearly time-specific. For Jesus says to his disciples:

Ye know that after two days is the Passover, and the Son of man is betrayed to be crucified.

Matthew’s use of “after,” unlike Mark’s introductory word (which is “de”), is the Greek word “meta,” which generally means “with” but can mean “after.” The reason we may suppose that Gr. meta in this case does not mean “with,” is because the 2nd day if counted inclusively would then be the next day, or the morrow [tomorrow], the simpler and more clarifying term Christ presumably would have used, if that is what he meant. Therefore here Gr. meta most probably means “after.” This means Jesus spoke on Wednesday daytime, so that after two days was Saturday, Nisan 15th. Moreover, “Passover” here must include the surrounding time of Passover, not merely the 15th of Nisan, else Christ did not fulfill the O.T. figure of the lamb slain on the 14th of Nisan. Let me give an example of Matthew’s way of speaking. Years ago, my wife and I would go to her parents for a Christmas Eve lasagna dinner; Christmas was technically the next day, yet I might say on December 22nd, “After two days is Christmas, when we eat lasagna at your mom’s house.” Here it would be understood that we technically do not eat lasagna on Christmas Day but on Christmas Eve, because my wife and I have a shared understanding of the events around Christmas. Even so, Christ and his disciples had a shared understanding that the Passover lamb was slain the day before the Passover, and so Christ’s statement about him dying at Passover would have been understood to mean the day before Passover. The original audience for Matthew’s gospel was Jewish, based on Matthew never explaining, as did John, for example, that the Passover was a feast of the Jews. Therefore Matthew expects his audience to understand that Jesus would be crucified the day before the Passover. And so Jesus is speaking on Wednesday daytime—two days after which is the “Passover,” i.e., Saturday the 15th of Nisan. Someone might object here that Luke 22:7 equates the 15th of Nisan as the same day on which the Passover is killed. The KJV renders “Then came the day of unleavened bread, when the Passover must be killed.” First, the word “Then” is actually “de” and should be translated “Yet”. The “Yet” refers back to the fact that despite Judas having sought opportunity to betray Jesus, the Passover was about to commence. The word “came” is aorist, which scholars say is technically not a tense, although the aorist is traditionally translated in the past tense. And the word “when” is actually the Gr. en, and can mean, in relation to locative time, “in,” “at,” “by,”, “about,” “against,” etc. I think it’s best to understand Luke 22:7 to mean, “Yet comes the day of unleavened bread, about [against] when the Passover [lamb] is killed. Luke’s intended audience was Theophilus, who is thought to have been a Greek noblemen or government official. If there was any confusion on Theophilus’ part about the day the Passover lamb was killed in relation to when it was eaten, the rest of the gospel of Luke would have clarified that for him. So then, it appears that John and Peter asked Jesus about the “last supper” on Wednesday the 12th, not 13th, of Nisan. The Scriptures appear silent about what took place during Thursday daytime (the 13th of Nisan). But Gregg points out that the Galilean first-borns fasted during the daytime of the 14th of Nisan and therefore made preparations on the 13th of Nisan, since all Galileans rested from work during the entire 24-hour period on the 14th. And so the day before the 14th of Nisan (i.e., Thursday, Nisan 13), marking the calm before the storm, may have seen Jesus teaching the people in the temple, or teaching the people but then afterward retiring with his disciples.

But someone might object that a natural reading of Mark would lead one to conclude that the Last Supper happened the very evening which immediately followed John and Peter’s preparations, since the Scripture says, “And when even was come he [Jesus] sat down with the twelve.” But as we shall see, the gospels of Matthew and Mark give the back-story of Mary’s anointing to explain why Judas Iscariot betrayed Jesus, that therefore it is not intended to be part of the main chronology, and that to heighten the narrative the two gospels portray these related events just prior to describing the actual betrayal. So it ought

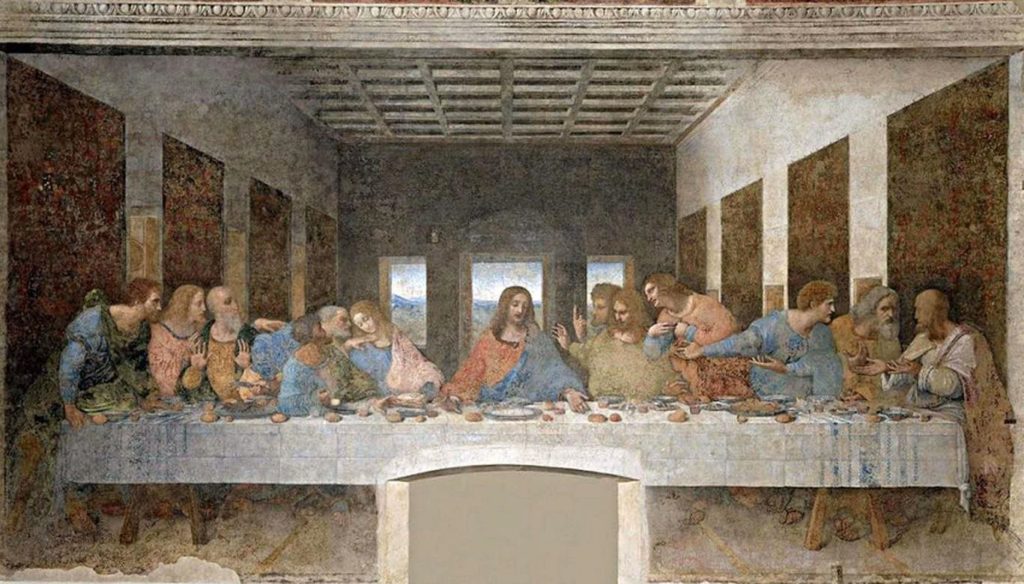

The Last Supper, by Leonardo Da Vinci. The 4th disciple from the left is Judas Iscariot, whose head is lower than the rest, and whom the artist put in darker light. Da Vinci, a master of perspective, conversely shows Christ much taller than the others if He were to rise from sitting (note the 4th disciple from the right is standing).

to be the reader’s expectation that the gospel writers should simply skip from Jesus’ description of Passover as just over two days away, to the evening of his betrayal, i.e. during the meal for which the preparation just spoken of pertained. In fact, Matthew in particular uses the Greek word “de” in 26:20 to more strongly connect the dots over the skipped day, in order to focus on the betrayal:

(19)And the disciples did as Jesus had appointed them; and they made ready the Passover. (20)Yet [Gr. “de” (unfortunately translated “Now” by the KJV) meaning despite Jesus knowing he would be betrayed by one of the disciples, he sat down with them anyway] when the even was come, he sat down with the twelve. (21)And as they did eat, he said, Verily I say unto you, that one of you shall betray me.

So then, John and Peter began making preparations for the Passover on a Wednesday, perhaps in the afternoon, since we are told Jesus had been for some days teaching the people in the temple in the mornings. Or else, since Jesus taught the people in the mornings, he may have instructed John and Peter before teaching in the temple. At any rate, again, Gregg shows that the disciples were not merely preparing for what they supposed would be the official Passover Seder meal just over two full days away on the beginning of the Jews’ normal sabbath (i.e., by western reckoning, Friday night), but also, as events proved, for a “last supper” meal on Thursday after sunset or at night. (We know at least that by the time Judas left the supper it was night (Jn. 13:30).

Incidentally, someone might object here by saying that the Last Supper and the official Passover Seder meal were one and the same, and that Jesus implied it by saying “I will not anymore eat of it, until it be fulfilled in the Kingdom of God,” implying that Jesus did in fact eat the official Passover Seder that night. But the word translated “anymore” is the Greek ouketi, and means no longer, no more, or no further. And with the ou me the negative is strengthened. And so Jesus is saying he will certainly not eat of it further, i.e., of the Passover observance the next night, until at some point in future history all is fulfilled in the kingdom of God.

(e) THE PASSION WEEK CHRONOLOGY OF MARK, FROM THE TRIUMPHAL ENTRY TO THE CRUCIFIXION

At this point we can work backwards from this Wednesday daytime of John and Peter’s beginning preparations (the day that Christ said Passover would be after two days) to show all the relevant time markers Mark gives us in 11:7-20, which in the end show that the Triumphal Entry was on Monday, the 10th of Nisan. However, it will be easier if we follow this chain of events from the Triumphal Entry described in Mark 11 and move forward.

The Triumphal Entry of Christ

So then, on Monday Jesus comes down from the Mount of Olives on the donkey brought to him by his disciples, who procured it according to the Lord’s instructions. It was a donkey upon which “no man had ever sat.” This refers to the unique place and seat of authority which Jesus alone among men ever occupied because of his obedient submission to the Father, with whom he was equal. The crowd lays its garments and tree branches before him and shouts Hosanna. Jesus enters Jerusalem and the temple, looks around, and now that it is eventide he departs into Bethany. This day exactly marks the completion of the 69th week of Daniel after which Messiah would be cut off, though not for himself, a fact the Jews should have understood from Daniel 9. Now observe that 69 weeks = 483 years of 360 days, or 173,880 days, which in standard (i.e. tropical) solar years = 476 years, 24.7 (ca. 25) days. Calculating backwards on the Julian Calendar from Monday, April 27, 33 AD (the date of the Triumphal Entry, and the 10th of Nisan) brings us to April 6, 444 BC. And so the beginning and ending ‘bookend’ dates of the 69 weeks of Daniel work out to (Julian) April 6, 444 BC to April 27, 33 AD, a period of 173,880 calendar days.

So on Monday, April 27, 33 AD, Jesus descended from the Mount of Olives into Jerusalem for his Triumphal Entry. In the evening he leaves the city for the nearby town of Bethany. “On the morrow,” Tuesday, Jesus comes from Bethany and discovers a fig tree barren of its earliest figs (known as breba). (Note: even as early as late April breba may appear on a fig tree in this region, especially if it is up against a house.) He curses it because its barrenness is a sign of Israel’s unbelief. He goes into Jerusalem and into the temple, where he begins to cast out the money changers. He then goes out of the City. “In the morning,” Wednesday, Jesus and the disciples again pass the fig tree, which has dried up by the roots as a result of Jesus cursing it. Again Jesus enters Jerusalem and the temple, and various groups confront him with their arguments, all of which Jesus refutes until they dare not ask him further questions. Jesus then begins to interrogate them, asking how the Messiah can at the same time be described in the Scriptures to be David’s son yet also David’s Lord? [Thus Jesus implies (1) the nature of his humanity, which came from his mother, who was a direct descendent of David the King, but also (2) the nature of his eternal pre- existence before his incarnation, which makes him David’s Lord.] Jesus then observes people giving their money offerings at the temple, and he remarks how the widow who gave two mites gave more than anyone else, since she cast in all she had. He then goes out and responds to his disciples’ remarks about the temple, and speaks of its coming destruction and of catastrophic events at the end of the age. He then utters additional sayings (Mt. 25) to his disciples before stating in Matthew 26:2 that after two days is the Passover, when the Son of Man is betrayed to be crucified. Here, again, we are reminded of how Luke conflates the day of crucifixion with the Passover of the next day, showing that Jesus was really speaking of Passover in the sense of Passovertime” (if that term will be allowed), even as we speak of Christmastime, though what is meant is not merely that time of Christmas day, but the time surrounding it.

(f) DID MARY ANNOINT JESUS TWICE? OR ELSE WHY DO THE GOSPELS SEEM TO PLACE IT ON TWO DIFFERENT DAYS?

Finally, we consider the charge by some critics that the gospels record Mary’s anointing of Jesus on different days of the Passion Week. To some extent we have already answered this charge by showing the role of the dative case in Matthew 26:17 and Mark 14:12. But let us examine in greater detail the three passages that tell of Mary’s anointing.

Woman Washing Jesus’ feet, by Heinrich Hoffman. Jesus said the perfumed anointing was for his burial.

Mary’s anointing of Jesus with precious ointment is told in Matthew 26, Mark 14, and John 12 (while Judas’s betrayal is told in all four gospels). Yet the narratives contain differences. Matthew and Mark state that Mary anointed Jesus’ head, while John says Mary anointed Jesus’ feet and washed them with her hair. Matthew and Mark say that the disciples objected to so costly a perfume; John only mentions that Judas objected. Matthew and Mark seem to place the event a few days before the Passover; John places it six days before it. Because of these differences some theologians think the gospels record two anointings, not just one. I suppose that is a possibility, yet I don’t personally incline toward this view. For one, Mary’s gift strikes me as singular and unique. There is the special alabaster box which is broken, the costly perfume, the indignation that money was being “wasted” (though Judas Iscariot’s objection was made in pretense), and Jesus’ statement that the anointing was for his burial. To me the idea of a two-fold anointing on two different occasions pertaining to a singular burial strikes me as redundant, if not inappropriate. Furthermore, it has long been known that gospel writers often emphasize different aspects of the same event. I believe this explains why Matthew and Mark wished to record the anointing of Jesus’ head, while John wanted to record the anointing of his feet and (presumably) also that Judas Iscariot led the disciples’ chorus of indignation against the ‘waste’ of costly perfume. But since I embrace the position that there was only one anointing, let me offer an explanation about why the gospels seem to place Mary’s anointing on two different days.

The solution, I believe, is that John’s record is the chronological one, while Matthew’s and Mark’s accounts of Mary’s anointing and Judas’s decision to betray are parenthetical ‘flashbacks.’ Evidence for this view is the role the Greek word “de” plays, which has been wrongly translated by the KJV. This narrative parenthesis in Matthew and Mark provides the reader with the background of the betrayal just before the actual betrayal is recorded, a literary device which sharpens the focus on the betrayal part of the narrative. Moreover, if the writing of the Bible is in fact superintended by the Spirit of God—a God who says he is not the author of confusion—then contradictions cannot exist in the original autographa of the Bible; and so the Matthew and Mark accounts of Mary’s anointing cannot have happened two days before the Passover, since John states it happened six days before the Passover (Jn. 12:1). Still, our faith in the Bible’s reliability must finally rest on reasonable evidence. (Exceptions for antinomies must involve God’s attributes, not humans in two places at one time!) Therefore, what reasons are there for believing the gospels are congruent on this point?

First, as we have already seen, the dative in Matthew 26:17 does not mean “Now the first [day] of the [feast of] unleavened bread,” and so does not act as a time locator for the narrative. Otherwise the “Now” would act to place the following story about Mary’s anointing on the first day of unleavened bread, or six days later than when John places it. But Matthew 26:17 should instead read: “Yet for the sake of the first day of unleavened bread….” Thus Mary’s anointing in Matthew 26 and Mark 14 should be regarded as parenthetical, because the “de” which begins Matthew 26:17, which Mark parallels in 14:12, has nothing whatsoever to do with placing the event of Mary’s anointing onto a strict, chronological timeline. Rather, it merely acts as an adversative and thereby a connective, in this case between two statements forming an irony, namely, about those who came willingly to hear the Lord, versus those who came to kill him. The irony in the narrative becomes even more profound when we realize that the Passover symbolized—but this year would actualize—the only way of escape from God’s judgment for even those enemies of Jesus who wanted to kill him.

So we see that Matthew’s and Mark’s accounts of Mary’s anointing of Jesus do not intend to show a pinpointed event on a strict, chronological timeline. Rather, they intend to show the irony of widely different responses toward Jesus, through the literary device of parenthetical ‘flashback’. Now to better help us see this irony in the narrative, especially as it relates to the betrayal of Jesus by Judas—brought on, so to speak, by Mary’s costly anointing—let me offer a translation (bold and underlined, to separate it from some interspersed explanatory notes) of Luke’s account of Judas’ betrayal in 22:1-13:

Luke 22:1-13

(1)Yet (Gr. de, an adversative meaning yet, but, nevertheless, etc., forming here a contrast to the closing thought of the previous chapter, in which it is stated that the people came willingly (desirously) to hear the Lord in the temple in the morning) the feast of unleavened bread draws nigh, being called the Passover; (2) and the chief priests and scribes keep seeking how to kill him! [impl. secretly] (For they remain afraid of (lit. keep fearing) the people.) (3)Yet [Gr. de, an adversative, i.e., implied, despite the chief priests’ and scribes’ fear of the people, which might lead to a defeat of their plans] Satan enters into Judas Iscariot, being of the number of the twelve. (4)And he goes his way, and communes with the chief priests and captains, how he might betray him unto them. (5)And they are glad and covenant to give him money. (6)And he promises and keeps seeking opportunity to betray him in the absence of the multitude, (7)yet [Gr. de, an adversative] comes (aorist ‘tense’, rendered “came” by the KJV, but the aorist is technically not a specific tense, and so is not at odds with our previous analysis that this conversation did not take place on the Day of Unleavened Bread) the day of unleavened bread when the Passover must be killed [implied, despite the feast being nearly upon them, an opportunity for Judas to betray Jesus has not yet come].

[new paragraph] (8)And he [Jesus] says to Peter and John, “On your going, prepare us (Gr. lit. to us, is in the dative, thus corroborating Matthew and Mark, that Jesus’ instructions are for the purpose of the Passover, not on the Passover) the Passover, that we may eat. (9)But [Gr. de] they say unto him, “Where do you want that we should prepare?” (10)Yet [Gr. de, implying (as we shall see after the narrative has unfolded) Jesus did not tell the disciples plainly where he planned to keep the Passover, because Judas Iscariot would then have brought the mob to that place and interrupted the Last Supper] Jesus says to them, “Listen closely! When you are entering the city a man shall meet you who bears a pitcher of water. Follow him into the house where he enters. (11)And you will say unto the goodman of the house, ‘The Master says to you, ‘Where is the guestchamber where I may eat the Passover with my disciples?’ (12)And he will show a large upper room which is being furnished: there make ready.” Yet [Gr. de] they went, and found [implied, exactly] as he had said unto them. [impl. despite whatever skepticism either Peter and John might have had about Jesus’ predictive powers of whom the two disciples would meet upon entering the City, and the importance of it, such foreknowledge by Jesus proved accurate (and thus readers who would be like Peter and John should take note!).] (13)And they make ready the Passover. And when the hour comes, he sits down, and the twelve disciples with him.