In verse 1 in the above translation, the Greek adversative de should not be translated “now,” but rather yet/but, to show a contrast between something previously mentioned and something about to be stated (the ironic responses of the Jews). (Incidentally, as just seen, “yet,” not just “and,” can express irony in some cases.) Therefore once the Greek word “de” is understood to mean yet, but, despite, nevertheless, etc., one understands the contrast begun in Luke 21:38. Note, then, the irony of contrast in Luke 21:38—22:2, given below without the interspersed marginal notes:

And all the people continue coming early in the morning to him in the temple, for to hear him; yet the feast of unleavened bread draws nigh, which is called the Passover, and the chief priests and scribes keep seeking how to kill him! (For they feared the people.)

So, while the people heard Jesus gladly, certain aggressive and ambitious leaders of the people hated Jesus and wanted him dead. (Even Pilate realized they were envious.) In this sense of irony Luke dovetails nicely with John’s use of the Greek word “de” (also unfortunately translated “now”) which opens up the beginning of John 13, which, when considered in relation to what John is contrasting it to (previously in chap. 12), shows that, despite the people not believing in Jesus though he showed them many miracles (12:37), and despite many among the chief rulers who did believe in him but were unwilling to confess their belief for fear the Pharisees would put them out of the synagogue (12:42), nevertheless Jesus loved his own even unto the end. Note here that the identity of those called “his own” is given to us by John at the beginning of his gospel in 1:11, when John observes with irony that the Word [Jesus] “came unto his own, and they received him not.” Thus John bookends all of his gospel prior to the Last Supper and the momentous, final events which follow it, by showing that, though Jesus came unto his own who received him not (Jn. 1:11), he nevertheless loved them unto the end, even when he knew the hour of his death was at hand (Jn. 13:1). The point in all this, insofar as the gospels of Luke and John, and the current point under consideration in this book are concerned, is that “Now,” when rendered from the Greek de, does not mean now, nor does it act as a temporal locative. Rather, it means “yet,” and, like the other gospels, at times emphasizes the paradox of Israelite response which was divided in its opinion about Jesus.

Having examined, then, the critics’ charge that there are contradictions in the timelines of the gospels, we find this accusation without substance. Of course we cannot stop people from disbelieving the gospels if they are determined to disbelieve. But from the evidence seen, we can say with sufficient confidence that the gospels are in fact reliably consistent in presenting Christ to be the Lamb of God, the Savior of the world, and the perfect fulfillment of the Old Testament symbolism of the lamb sacrifice.

(g) FURTHER SIGNIFICANCE OF THE 10TH OF NISAN

Finally, concerning the 10th of Nisan, note that Jesus utters a remarkable statement on this day as he nears Jerusalem while riding on a donkey:

Luke 19:41-42

And when he was come near, he beheld the City, and wept over it, saying, “If you had known, even you, at least in this your day, the things which belong unto your peace! yet now are they hid from your eyes” (NASB).

Thus Jesus refers to this day of his Triumphal Entry—which he calls their day, i.e., the Jews’ day—as the time when they should have recognized the Messiah’s coming. This is because if they had they been counting off 69 weeks (483 years of 360 days each) since the time the commandment went forth to restore and build Jerusalem—the very City he now was about to enter for the purpose of bringing it peace—they would have known that Messiah would afterward be cut off, yet not for his own sins. The cutting off of the innocent at this time of year for sins not his own (since he had never sinned) therefore implied God’s Passover sacrificial Lamb, scheduled to be killed on the 14th of Nisan, 33 AD. And therefore the Jews should have been looking for God to show in some demonstrable way the setting apart of that Lamb just before that, which according to Old Testament symbolism should occur on the 10th of Nisan. And, indeed, in 33 AD there he was! But because Christ’s own race had not set their hearts to know the time of Messiah’s cutting off, they did not recognize him at his coming. And so Christ—who on that Passover could have been sacrificed by a believing people, i.e., without any particular malevolence on their part but with knowledge that the Messiah would need to die, even as Abraham committed himself to sacrifice Isaac upon the altar without any malevolence toward him—was instead rejected.

Likewise, most Gentiles today reject Christ. There is wholesale ignorance of the prophecies concerning the Messiah in the Old Testament, including that of Daniel 9:25-26a. But indeed, each of us has been oblivious to such truths at one point or another. And so each has lost himself or herself to some anxious- minded business in this cared-filled world consumed with its own transient ways, and ignored the Messiah who sacrificed himself for us. But having read here of the prophecy of Daniel, perhaps some reader now feels differently about the matter. If so, let me encourage him or her to act on this conviction now and tell the Messiah you recognize his sacrifice for your sins. For although he was cut off from this world, he raised himself on the third day, the day of the First Fruits Offering according to Old Testament symbolism, so that he might be the firstborn from the dead (Col. 1:18). For he will surely save all those who trust in him.

It is an amazing thought to realize the Messiah is alive even as you read this. And his life is in himself, as he said. For in Mark 10:34 we are told that Jesus took his disciples aside to tell them the Son of Man would be killed, and would rise the third day. Here the verb “rise” is in the middle voice in Greek, meaning self- reflexive action. That is, Jesus was not saying he would be raised (though elsewhere he did state that God would raise him). Rather, in Mark 10 Jesus is saying he would raise himself. Now, we know that no mere creature is able to raise himself from the dead, any more than a mere creature could conceive the prophecy which was delivered unto Daniel about a coming Messiah who would be cut off.

Now observe that one of the characteristics of the Creator is that, although he draws all people to himself, he paradoxically wants to be searched out and found. This is why the Messiah was sent—to help people find God. Combining the insights of Genesis 1 and John 1 we know that the Father, the Son, and the Spirit were all Persons involved in creating man, and then reaching out to him. “Without him [the Logos, i.e. Christ],” says John, “was not anything made that was made…And he came unto his own….” Yet despite his pre-human, eternal existence, the Son humbled himself to do the will of his Father. (The term “Son” refers to Christ’s function, not to any ontological or chronological inferiority to the Father.) Now note that though Jesus said he would only do what his Father showed him—and in fact did many miracles while on earth—he refrained from doing the kind of miraculous signs and wonders in the heavens that the Jews of his own generation demanded a Deity should do, to prove his pre-human existence. Instead Jesus said the only sign they would receive was the sign of Jonah—i.e., that the Son of Man would be in the earth [but for] three days and three nights. For imagine the likely outcome had Jesus condescended to his generation’s demands for miraculous signs in the heavens. Surely people would have ‘believed’ for the wrong reason. That is, they would be afraid that anyone powerful enough to perform such miracles in the heavens could easily kill them, were they not to confess that he was God. And so, while they would hasten to confess Jesus to be God, and even for fear and for ‘brownie points’ confess him to be a good God, many would not really believe he was good at all, but that he was merely coercing their confession under threat. This is why God does not legitimize confessions motivated solely by threat. He wants people to believe in and confess to his goodness without putting them under coercion. This stands in stark contrast to the method of numerous evil rulers and their minions throughout history. These have tortured persons into making false confessions, something these interrogators seem to value even more than their own blueblood confessions, taking, as they do, a perverse pleasure in them.

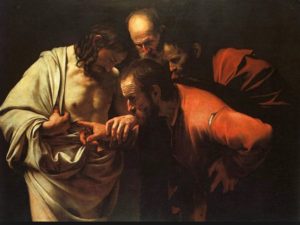

The Incredulity of St. Thomas, by Caravaggio. “Then He said to Thomas, “Reach here with your finger, and see My hands; and reach here your hand and put it into My side; and do not be unbelieving, but believing.” Thomas answered and said to Him, “My Lord and my God!” (Jn. 20:27-28; NASB)

Yet someone may object: “But God does coerce if he promises to punish all who disbelieve.” But the suffering of God’s judgment comes after this life, not during it. And Ecclesiastes states just how much (or little) effect God’s mercy has on us:

Because sentence against an evil work is not executed speedily, therefore the heart of the sons of men is fully set in them to do evil (8:11).

The exception of judgment in this life is when God judges a people or nation after generations of disobedience, like that which came upon the people in Noah’s time. Yet God had given the people of Noah’s generation 120 years to repent after he saw that men’s hearts imagined evil only. The point is, God is not merely patient but also just; and therefore he must at some point punish evil, or else be unjust. But nowhere in the Bible does God hastily bring judgment. For the Scripture says, “All day long I have reached out my hands to a disobedient and accusatory people.”

CONCLUSION

About once a month I get dinner with a friend of mine who believes all religions are the same. Yet he hadn’t always thought they were. But one day he exited church and looked across the street and saw a man mowing his lawn, and he wondered why that man should be excluded from the ‘in’ crowd—his crowd, the church crowd, the crowd that believed in Jesus. This was the beginning of what would prove to be my friend’s disbelief in the exclusivity of Christ. For he grew convinced there was no evidence whatsoever proving the superiority of any view, Christianity included. Now, whether his unbelief derived from (1) a general ignorance of biblical prophecy, which could have helped his belief in God, or (2) the cares of this world which choke the Word, or (3) a gnawing doubt about the exclusivity of Christ until the Bible’s message became nonsense to him, I don’t exactly know. But I suspect it was a combination of these, perhaps with the failure, so epidemic these days, of ignoring the advice of Daniel’s famous contemporary, Socrates, who said that every statement should be tested to see if it were true.

Today’s culture of apathy toward finding ultimate answers makes it harder for a person trying to find God. Too many ephemeral voices and images from TV and the internet swamp his or her attention. Added to all this meaningless overflow of information is the world’s fragmentation through technology and device. Often, too, there is little spiritual support from family, friends, the workplace, and even the Church. And so the seeker is discouraged from finding God—the Rock, the Refuge, the Safe Harbor for his soul. Rest—where is it? And how could an ancient Bible possibly be relevant to him today, amidst the bewildering complexity of 21st century life?

This last question becomes rhetorical in the mouths of academia and pop-culture notables, who know that the shortest path to convey the absurdity of a view is to ignore the subject altogether. Of course there is a vague allusion to the Bible on those rare occasions when the name “God” is drug out of the cobwebs. It happened, for example, in the political realm immediately after 9/11, when Congress buried the partisan hatchet just long enough to sing God Bless America on the Capitol steps. But the stun passes, like surviving a blow on the head, and the nation goes back to its true self. As a New York City bus driver told me a few months after the Twin Towers tragedy: “For a while people were really patient with the buses…but after about two weeks they were back to complaining like they always had.” Ever goes the world along its predictable way, to what has been called—to borrow a phrase—“the tyranny of the urgent.”

But we seek better things. Eternal things. Perhaps for the first time you have become aware of Daniel’s prophecy in the Bible about Jesus the Messiah, and are ready to believe. Daniel tells us that Messiah was cut off, but not for himself [i.e., for his own sins] (Dan. 9:26). This means it was for our sins for which Christ died. “Who His own self bore our sins in His own body on the tree…” says the apostle Peter (I Pet. 2:21). It is in Christ’s sacrifice alone that we find rest in God. In fact, this is why the apostle Paul said that if atonement could come through our own works, then Christ died in vain.

However, many people reject that God’s grace is obtained by a simple trust in Christ. These many are therefore under the condemnation of God, since no other sacrifice can atone for sins.

And so, too, did divine judgment loom over many of the people of Jeremiah’s day, for the people had been disobedient for a long time. Commonly, when we think of disobedience, we think of the more obvious sins. At first glance it seems strange to us that God would exile the Jews for, of all things, not allowing the ground to rest every seventh year from agricultural pursuit. We think it should have been for the people’s hypocrisy and deceit, or for their adulterous and murderous ways, etc. And certainly in one sense all these were

Jeremiah Weeping Over Jerusalem, by Rembrandt. The city’s destruction and the prophet’s grief form the theme of the book of Lamentations.

causes for why God delivered the Jews into the hand of the Babylonian king. But the point God was making by citing the Jewish failure to give Sabbatical rest to the land was in principle the same contention which Christ had with the people of his own day. Namely, the question was whether a man could achieve by himself a true rest, or whether that rest must come through God. The former is where man thinks he will find rest for his soul through mere, created things. In today’s world this method takes more than one form. It can take the ironic route in which man imagines his repose comes through material abundance, the kind brought about by a ceaseless tread on the 24/7 hamster wheel of work and acquisition. Another form is where the preservation of material nature is paramount. This is where any sacrifice is expected for the environment, both personally and societally, until the terrestrial world improves to whatever ideal standard the ideologues demand, which, of course won’t ever be perfect enough.

This misguided emphasis on the material is why Christ in his own day departed from the crowd of thousands after miraculously feeding them material bread. For he perceived they would come to make him king because of it (Jn. 6:15), since they didn’t want to work for their food. So he traveled to the other side of the Lake of Galilee. But that was not far enough away for a crowd who, as far as it was concerned, had literally just gotten a taste of what it would be like to live by bread alone. And so when they found Jesus they contended with him, that he should do as Moses had done, who fed their ancestors [manna] daily in the wilderness. But Jesus corrected them, telling them God, not Moses, had fed them, and that they should instead seek the Manna from heaven which the Father provided, namely, the Son himself. But as events proved, Christ’s generation rejected him, as had many (though not all) Old Testament generations of Jews in their rejection of the LORD. Some of the people were fearful, not trusting God to make sufficient provision in six years the needs for seven, while others were just greedy and so abused the land through overuse. And so in effect, Christ warns his hearers not to live by bread alone, i.e., not to focus on physical or material needs, but to seek the Manna from Heaven which they must ‘eat’ (i.e., receive by faith). Thus by receiving Christ there becomes provision for the soul, not just the body.45

Now, the Messiah of the Jews is a Messiah for all peoples. For the well-known Scripture of John 3:16 does not begin “For God so loved the Jews,” or “For God so loved Abraham’s descendants,” but rather, “For God so loved the world….” Yet all must come to God as Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob did, through faith.

The good news in all this is that we can find rest in God’s provision, the Messiah—the Manna from heaven, so to speak—without vainly trying to earn that rest. Indeed, God’s rest is ultimately the focus of Daniel’s prophecy about the coming of the Messiah, i.e., that we can find rest in God. As Paul says: “So there remains a Sabbath rest for the people of God” (Heb. 4:9, NASB). Here Paul is referring to a future, permanent rest for believers.

Therefore let all who trust in the Messiah for the forgiveness of their sins look forward to His Second Coming (since He has promised to return), with a similar anticipation to how the Jews were to have looked for His first coming. And may we share this message to all those who haven’t yet found rest in the Messiah.