Chronology Of The Hebrew Kings

Readers may wonder why in this book I should include a synchronization of the Hebrew Kings. My answer is that it defends a key assumption in this work, namely, that the writing of Kings and Chronicles was done from a consistent Tishri to Tishri perspective. Although the two evidences for this were given earlier in this book, let us recall them. A perspective of Kings and Chronicles is necessary so that the Bible can be shown internally consistent with itself. For if the internal biblical records about Jehoiachin’s surrendered and deportation cannot be harmonized, there remains a question about which year Jehoiachin was captured, in which case the identity of the 3rd year of Jehoiakim, when the exile began, cannot be known. And so an exact chronology is necessary to uphold the claim that the exile could not have been longer than a little over 69 ‘normal’ years. In short, unless a proper timeline can be established, neither can Daniel’s prophecy of the coming Messiah.

My concern about synchronization grew out of the frequent claim in Wikipedia and elsewhere online that Edwin Thiele, a Seventh-Day Adventist missionary and professor, had in 1950 (in a doctoral dissertation) solved the long-standing problem of synchronizing the Hebrew kings. Unfortunately, Thiele proposed that the Kings and Chronicles were not written from a consistent Tishri to Tishri perspective. But as noted earlier, this is necessary to the argument here about how to resolve the key ‘discrepancy’ that ultimately bears on the Daniel 9 prophecy about the then future death of the Messiah. The discrepancy in question is that Jeremiah 52:28 (and the Babylonian record) puts the deportation of Jehoiachin in Nebuchadnezzar’s 7th year, while II Kings 24:12 puts the surrender of Jehoiachin in Nebuchadnezzar’s 8th year. But obviously a deportation cannot happen in a year previous to that of the surrender. Thus this whole matter goes to the point about the reliability and internal consistency of the Scriptures, and, specifically, whether a timeline arising from a consistent Tishri to Tishri perspective in Kings and Chronicles supports the idea that the exile could not have been longer than about 69 years 4 weeks. Now as already noted in Chapter 3, such a length for the exile is compelling evidence that Christ had expected the Jews to count off Daniel’s 69 ‘weeks’ in years of 360, not 365+ days.

To this end, recall that Nebuchadnezzar ascended in early September, 605 BC, i.e., about a month before Tishri (the 7th month) that year, and so would have been reckoned in his 8th year by the time Jehoiachin took the throne in December, 598. This solution, though a straight-forward way of cutting the Gordian knot, has never been recognized by Thiele and his followers, who run into problems because of their belief that Jeremiah must have reckoned from Tishri to Tishri as a Southern kingdom prophet. Thiele et al are incorrect here, for they have failed to note that Jeremiah 28 places the 7th month in the same year as the 5th month, showing Jeremiah followed a Nisan to Nisan calendar. Indeed, a quick search of Thiele’s scriptura index to his landmark book, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, shows no mention of Jeremiah 28. And Thiele nowhere offers an alternative explanation for this passage. Instead, he appeals to the beginning date of Josiah’s extensive reformation of the temple, and believes so short a period of time could not accommodate the work prior to the Passover. I found this a somewhat reasonable argument yet ultimately realized it was incorrect in light of Jeremiah 28, since Jeremiah and Josiah were contemporaries and therefore would have observed the same calendar.

Sentry spots Jehu on the way to kill King Jehoram of Israel. Jehu also ended up killing Ahaziah of Judah. The year was 848/7 BC.

Thiele also believed the Southern kingdom generally used an accession year system, whereas the Northern kingdom often did not. In fact, our model shows which Northern Kingdom rulers were the exceptions who had either an ascension year or a delay in rule. They constitute 5 of the 19 kings of the Northern Kingdom. The first is Jehu, who was anointed by Elijah the prophet. We know Jehu had an ascension year because of cross-references with the Southern kingdom (see note under the year 848, following the chart below). The second is Jehoahaz, son of Jehu, who may also have had an accession year or a delay in reign until Tishri 1, or else began reigning on Tishri 1, since the beginning of his reign comes one year after the end of his father’s reign. The third is Menahem (see notes under the years 761 and 760, following the chart below). The fourth is Pekahiah, Menahem’s son. The reason for an accession year for Pekahiah runs thus: to suppose that the writer of II Kings would not have caught what would otherwise be a glaring mathematical mistake (were he using a consistent non-accession year reckoning for the Northern Kingdom, which some suppose) —recording, as he did, the 10-year reign of Menahem as beginning from Uzziah’s 39th year until his son/successor Pekahiah reigned in Uzziah’s 50th year—is implausible, given the writer’s attention to detail in every other respect. In fact, because Menahem’s reign had to have ended by Uzziah’s 49th year (and then only if we assume that Uzziah’s 39th year was an ascension year for Mehahem), Pekahiah’s beginning of reign in Uzziah’s 50th year demands the assumption that Menahem died before the turn of the year marking Uzziah’s 50th year (i.e., before Tishri, from the exilic author’s perspective). Thus Pekahiah began his ascension (or experienced a delay in rule) until on or after the turn of the year (Tishri 1) that marked Uzziah’s 50th year. (Here we use the phrase, “the turn of the year” as reckoned by the historians who wrote Kings and Chronicles, who seem to have used Tishri 1 to reckon regnal years rather than the beginning of the agricultural year, which began on Tishri 10 (discussion in Chapter 7, under “sabbath markers”).

These five exceptions that prove the general rule that Northern kingdom rulers used non-accession reckoning does not greatly concern me, since the ‘conflicting’ years of Nebuchadnezzar’s reign regarding Jehoiachin’s overthrow involves Southern kingdom citations only (i.e., by Jeremiah and the exilic author(s) of II Kings). As a reminder to readers, the accession year system of the Southern Kingdom is one in which the sum of sole regnal years across rulers is linearly preserved by the appearance of monarchs’ complete years of reign, when in fact the monarch usually does not complete his last year.

Again, the importance in all this is its application to the key assumption made earlier in this book, which, if correct, resolves the so-called biblical discrepancy of Nebuchadnezzar’s years regarding Jehoiachin’s surrender and deportation.

Ahab dies in battle (859/8 BC).

Moving on, we must show why Thiele was wrong to suppose that the “Ahab of Savhalla” in the Assyrian limmu lists was Ahab of Samaria. This assumption led Thiele to state that the Hebrew writers were in error. (Note:

the Assyrian eponym canon is a linearly formatted, year-by year Assyrian timeline.) So then, we must set out to see (1) if the Bible set forth an internally consistent synchronization of the Hebrew kings; and (2) if so, whether the exilic author(s) of Kings and Chronicles used a consistent Tishri to Tishri perspective in retelling the histories of both the Southern and Northern kingdoms (since it would seem strange to suppose any contemporary writers would adopt two [alleged] perspectives in these books, since two kingdoms’ calendrically intersecting events on the bases of a double-dating system would confuse the reader); and (3) whether such a harmonization of the Hebrew kings, formed solely on statements in the Bible, proves the Assyrian eponym canon harmonious with the biblical timeline of Hebrew kings, including Ahab of Samaria. I believe the research will prove all three of these points.

THE MEANING OF “REIGN”

At this point we must briefly address the meaning of “reign” in the Kings and Chronicles. It has, in fact, a wide latitude of meaning. For example, in one case we are told that Jotham reigned 16 years, yet in another place there is reference to “the twentieth year of Jotham.” How to explain? I think the best answer is that although “reign” sometimes has the formal definition of who technically is the king, other times it appears the definition of “reign” has a more practical meaning in view. To this latter point, a number of father/son co-regencies exist in the Hebrew chronology, and in some of them the father no longer appears to be wielding the practical, day-to-day rule. Generally, at least, we do not know the reasons for this. There may have been times when kings with illnesses could not practically manage the State. Or it may be that a co-regency began when a king went to war or desired a smooth succession. And so a king’s “reign” may begin or end upon a number of points: (1) most typically, the beginning of a reign commences in the same

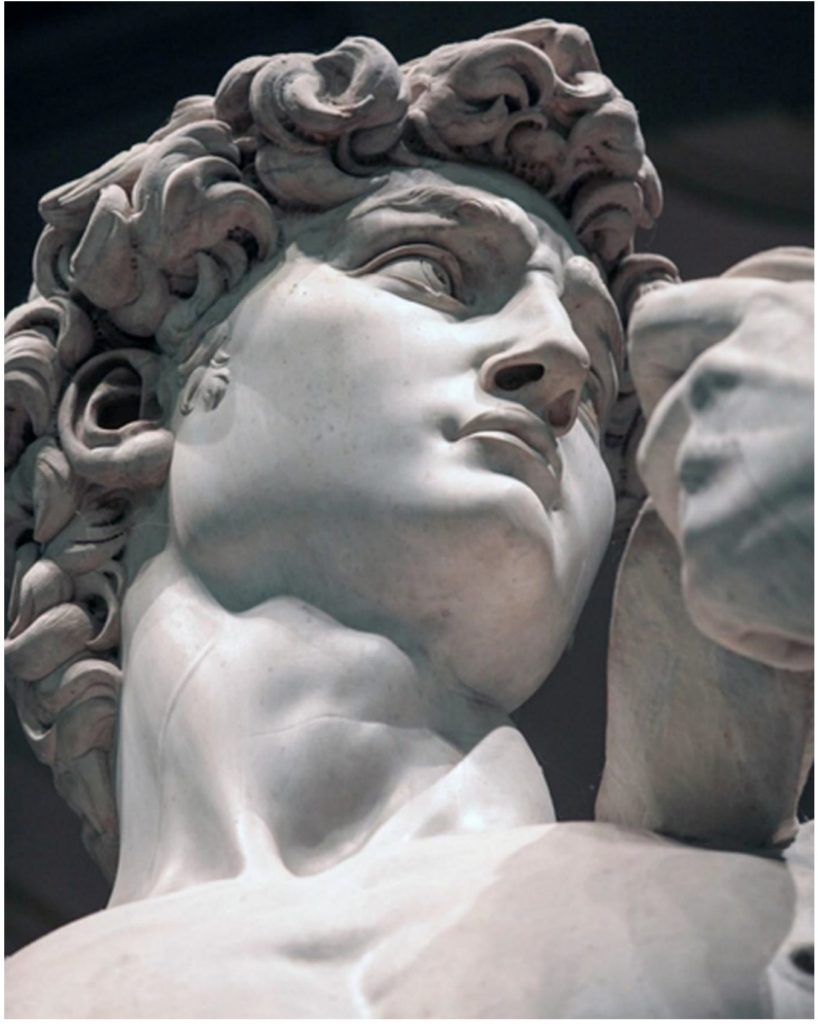

The Judgment of Solomon, by Nicolas Poussin (1649). God gave Solomon wisdom and knowledge to rule His people Israel. The year was 966 BC. Solomon was the 3rd and last king of the United Kingdom of Israel, and ruled for 40 years.

year the previous ruler died; (2) the beginning of a reign may commence with a son’s elevation to co- regency; (3) the beginning of “years reigned” may come after a period of co-regency which, for some reason, the biblical author does not include as part of the number of years reigned. (Note: in such a case the year is not arbitrarily assigned in the below chart: it is deduced from at least one cross-referencing statement.); (4) “reigning” may be said to occur both upon the ascension year, and the year solo reign begins. This is the case with Ahaziah (Judah), who apparently co-reigned during the last two years with his father, though in the end father and son died in the same year, though the son died after his father after a brief solo reign; (5) the years of “reigning” may be counted after a co-regency commences, yet also end before the king’s actual death. This occurs with Jotham of Judah, son of Uzziah (Azariah), whose 16 “years reigned” is sandwiched between a 20 year period, with one of the 20 coming before, and three of the 20 coming after, the 16-year period. The reason we know this, in this case, is the same reason we often know anything at all about synchronization: it is found in the cross-referencing statements between the two kingdoms. Yet sometimes it is not only this. It can also involve whatever logical deductions should be made from the text. For example, in the case of Ahaz, father of Hezekiah, there are two statements seemingly discrepant. The first is that Ahaz reigned in the 17th year of Pekah, the second is that Pekah’s 20th year was Ahaz’s 12th. But only the latter of these makes possible an age conceivably old enough for Ahaz to have sired Hezekiah. And so in this case the statement that Ahaz reigned in Pekah’s 17th year cannot refer to the absolute beginning of Ahaz’s years reigned, since this would mean both Ahaz and his son, Hezekiah, would be 25-years old in the 3rd year of Hoshea (when Ahaz died). Therefore the statement that Ahaz reigned in Pekah’s 17th year must refer to the reign Ahaz began in the year Jotham’s 16-year practical reign ended, meaning (a) Ahaz had begun his co-regency (i.e. ascended) 12 years before Pekah’s 20th year, and (b) Jotham technically remained king for another 3 years past Pekah’s 17th year, such that Jotham’s “20th year of reign” ended with Pekah’s 20th year of reign (see chronological table). Finally, (6) no co-regency should be assumed unless implied by another biblical statement (or statements) that makes it necessary or very likely. For example, since (a) Jeroboam reigned 41 years and was succeeded by his son, Zachariah, and since (b) Zachariah reigned in Uzziah’s 38th year, and since (c) no biblical statement suggests Zachariah ever reigned previous to Jeroboam’s 41st year or Uzziah’s 38th year, then no co-regency should be allowed for Zachariah. Unfortunately, Edwin Thiele allows one particular co-regency on dubious grounds. He believes that Pekah, who came to power after killing Pekahiah, had previously reigned a nation called Ephraim (see Thiele, chpt. 3, fn. 1), not only during Pekahiah’s 2 years of reign but also during the 10 years of Menahem (Pekahiah’s father and predecessor). Again, there is no warranty for such suppositions. Thiele only assumes this because he believes a certain “Ahab of Zirhala” in the Assyrian record was the biblical Ahab, and so he needs to compress the years of the biblical narrative to make his timeline work.54 So I believe Thiele was incorrect here. So also was his idea that Manasseh was 12 when he co-reigned, an assumption the Bible gives no warrant to make.

However, elsewhere Thiele did find a unique solution to the oft-claimed discrepancy of II Kings 15:1, in which Uzziah “reigned” in Jeroboam II’s 27th year. Thiele realized both Uzziah and Jeroboam II’s co- regencies should reach back earlier to include years not very apparent in a superficial reading of their regnal years. Although at least one of Thiele’s assumptions is wrong about which years a ruler ruled (Thiele believes Jehoash (Israel) began reigning upon the year of Joash’s (Judah) death [40th year] instead of in Joash’s 38th year [on the assumption that Amaziah’s (Judah) ascension (see II Ki. 14:1) happened upon the death of Joash rather than in Joash’s 38th year), nevertheless Thiele is correct in stating that Jeroboam had a co-regency of 12 years, and that Amariah [Uzziah] had a co-regency of 24 years. Says Thiele:

We have shown that the death of Amaziah in Judah took place 15 years after the death of Jehoash in Israel. But by that time Jeroboam had already reigned 27 years, for Azariah’s accession is dated in the twenty-seventh year of Jeroboam. That being the case, it is clear that Jeroboam must have reigned 12 years contemporaneously with his father before the latter died. It is this 12-year coregency of Jeroboam with his father Jehoash that is responsible for the excess of 12 years in the totals of Israel over Judah at this point. Once this coregency is recognized, it will be clear that the “flagrant contradiction” of which the Biblical writer has been here accused exists only in the mind of the critic.

The next point of comparison comes with the death of Jeroboam after a reign of 41 years and the accession of Zachariah in the thirty-eighth year of Azariah (II Kings 15:8). Since Azariah’s accession at the time of his father Amaziah’s death is dated in the twenty- seventh year of Jeroboam, and since Jeroboam reigned 41 years, it will be clear that Jeroboam died and Zachariah came to the throne 14 years (41 less 27) after Amaziah’s death. But since Zachariah’s accession is dated in the 38th year of Azariah, it will also be clear that Azariah had at this time already ruled 38 years. If his father, however, died only 14 years before that time, then the reign of Azariah must have overlapped that of his father 24 years (38 minus 14). Once this is understood, it will be clear why the total regnal years of Judah for this century are 24 years in excess of the contemporary Assyria, as Albright has correctly declared. The cause of the excess, however, is not an error in the Biblical data but simply an overlapping of reigns.

The King Uzziah Stricken with Leprosy, by Rembrandt (1635). God struck Uzziah [Amariah] when he bypassed the priesthood and personally offered incense. II Chronicles 26:21 implies Jotham then took over his father’s duties.

When once it is understood that the reign of Jeroboam in Israel overlapped that of his father Jehoash 12 years, and that the years of Azariah overlapped those of his father Amaziah 24 years, the supposed insoluble chronological difficulties of this century disappear, and harmony rather than “flagrant contradiction” is found.

Thus the co-regency of Jeroboam (II) runs for 12 years, which in the chart below begins in Jehoash’ 5th year, and the co-regency of Uzziah (Amariah) runs for 24 years, beginning in Amaziah’s 5th year. And so when II Kings 15:1 tells us that Amariah (Uzziah) began to reign in Jeroboam’s 27th year, we may understand this to mean that Amaziah’s sole regency began in the 27th year as reckoned from the beginning of Jeroboam’s co-regency. Likewise, we may understand the seemingly biblical contradiction derived from other biblical verses, i.e. that Uzziah’s reign began only 3 years after Jeroboam’s reign. This 3-year difference is based on Jeroboam reigning 41 years (II Ki. 14:23), Zachariah reigning when his father Jeroboam died (II Ki. 14:29), and Zachariah reigning 6 months in Uzziah’s 38th year (II Ki. 15:8). But here the resolution is that Jeroboam’s 41st year is Uzziah’s 38th year because the reckoning of both kings is from the beginning of their co-regencies with their fathers. These, then, are legitimate co-regencies to assume, since other biblical statements make the deductions necessary.

But as for Thiele’s alleged kingdom of Ephraim, surely if the Bible bothers to tell us that the kings Zachariah and Shallum ruled 6 months and 1 month, respectively, then it could hardly omit so momentous a matter as to tell us if Ephraim was its own kingdom with its own kings, as well as omit cross-referencing statements of such a kingdom with the regnal years of the Southern and/or Northern kingdoms to prove this. And so, for example, our model disagrees with Thiele’s belief that Pekahiah ever ruled an alleged kingdom of Ephraim. Therefore such alleged co-kingdoms or co-regencies without any real supporting biblical bases should be rejected.

At this point let us map out the other discussion points we want to consider. We will see why Thiele was incorrect about certain assumptions he made, including a refusal to recognize straight-forward, biblical statements about Hezekiah and Hoshea having intersecting reigns. Following this will be a table showing the reigns of the Hebrew kings year by year. After the table are some notes to help explain the placement of each king, and to address any remaining problems about synchronization that seem to arise from the biblical text itself. Again, I believe the most significant contribution Thiele made to the study of the Hebrew kings was his solution to the II Kings 15:1 problem of harmonizing the reference to the 27th year of Jeroboam II in relation to other statements. This was a great insight. On the other hand, Thiele was wrong to suppose (1) the reigns of Hezekiah and Hoshea did not intersect; (2) the Southern Kingdom reckoned from Tishri; (3) that the “Ahab Zirhala” of the Assyrian record was the biblical Ahab; and (4) that Ephraim was a separate kingdom with its own king. Incidentally, the following critical remarks address Thiele’s system, not the modified version of Thiele’s system by his followers, which some scholars follow.